Former football Academic All-American honors mother, stepmom with gifts to athletics, the arts

Mike Wade

Mike Wade, a former two-time Academic All-American at Western Carolina University, will tell you that football is the greatest metaphor for life: to survive you have to get back up every time you get knocked down — and you will get knocked down, he insists, many, many times.

But Wade got knocked down hard at an early age — well before he started playing football at McDowell High School. He was just 6 years old when his mother died of cancer. She was 31, the mother of three. Billie Wade’s death was a tremendous shock for her middle child, a profound loss for a little boy with a tender heart. He eventually got back up, but it took him 38 years to recover from the crippling grief he just couldn’t shake. Thankfully, his father and new stepmother, Barbara, kept him grounded — just enough.

“I was very fortunate,” said Wade, now 63. “I grew up with a father who played professional baseball. He had a lot of expectations for his kids. There were no excuses. You get up, you go to school, you try to excel in everything that you’re involved in. If you’re going to be involved, excel in it.”

Wade did excel, so much so that he recently made a $1 million planned gift to support WCU’s athletics and arts scholarships and programs — one of the largest gifts given to the Catamount athletics program and one of the largest gifts ever by a former student-athlete. He created two endowed scholarships and named them after his mother and stepmother: The Billie and Barbara Wade Endowed Athletics Scholarship, with an estimated gift commitment of $450,000, for WCU student-athletes, and the Billie and Barbara Wade Endowed Arts Scholarship, with an estimated gift commitment of $50,000 for students majoring in a program in the David Orr Belcher College of Fine and Performing Arts.

He said he is grateful that he is in a position to help WCU’s “Lead the Way: A Campaign Inspired by the Belcher Years” reach the $58.7 million mark and honor loved ones at the same time.

“I have an incredible father, just the greatest dad that a son could have,” Wade said of his 90-year-old father, Gale, a former outfielder for the Chicago Cubs. “But he would have been embarrassed if I would have named it after him. He is not a guy who likes the limelight.”

Wade also pledged another $450,000 to the Athletic Director’s Fund, another $50,000 to the Belcher College of Fine and Performing Arts Dean’s Fund and $27,500 to the Catamount Club.

“My mother died at 31 years old, so she didn’t get much of a shot,” Wade said. “She was such a loving person. I just remember her touch, the feeling of her holding me. And I can remember her being very sick and watching her die. I wanted to honor her by saying, ‘Hey, you had a family and they’ve all done well. All of us have been able to achieve things.’ She brought us here, she gave us an incredibly loving place for six years.”

Wade’s stepmother was just 21 years old and still a college student when she married Wade’s dad, who was 33 at the time. They met when she worked on Gale Wade’s unsuccessful campaign for sheriff. “She was getting certified as a teacher and still had another half a year left to go in school,” Wade said. “To think this lady would come in to our house with three young kids and she wasn’t even finished with school. She gave up a lot of her life to take care of us. She was so highly accomplished. She was not only a great teacher, but a wonderful artist, too. I wanted to make sure I endowed at least one scholarship for the arts. She is very happy about that.”

Billie and Gale Wade’s middle child didn’t always have the money to give to others. The boy — who beginning at age 7 until he left for college had to rise at 5:30 every morning to milk the family cow — suddenly found himself a long way from where he had been raised, and he didn’t like it. “I was broke at age 28,” he said. “And the cavalry wasn’t coming.”

Wade remembers the moment he committed to changing his life. “I can remember sitting in the house. I had done all of these things and I really had a good base. I had no excuse for being in the situation I was in. I remember sitting there and I said to myself, ‘You are going to do what you were taught. You’re going to put your nose to the grindstone. You are going to work and you are going to get out of this mess that you put yourself in and you will never be broke again.’”

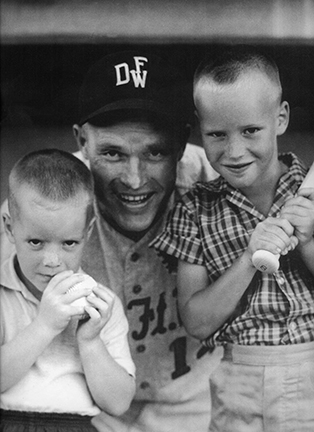

Mike Wade (right) is shown with brother Scott and father Gale Wade, who played with the Triple-A Dallas-Fort Worth Rangers of the American Association, in late July 1961 at the former Owen J. Bush Stadium in Indianapolis. Mike Wade eventually played football for Western Carolina University and Scott Wade played football for North Carolina State University and the University of South Carolina.

About 20 years later — at age 47 — Wade retired from the insurance business in Florida, where he had been living for the past 16 years. He took the proceeds from the sale of his company and used it as seed money to start a new chapter in his personal and professional life: Rabbit Ridge Properties, off-campus housing for WCU students, which opened with 44 beds in the fall of 2003. The property now has 298 beds. At one point, before the complex grew so large, Wade knew the name of every student living there. He wanted to; it was important to him.

“I love being in the student housing business,” said Wade. “I enjoy that age group, because I had so much fun between 18 and 22. These kids aren’t perfect, but most of them are fantastic kids. They’re just trying to find their way like I was when I was at that age. I can put myself in their shoes. They’re trying hard. Yes, they make a few mistakes here and there, but that’s OK.”

Wade, who has been married to Regina Wade for seven years, has no children of his own. He said he gets misty-eyed talking to some of the students who live at Rabbit Ridge, hearing their stories of how hard they’re working to put themselves through school, with little or no parental support. “Not because necessarily they’re bad parents, but because they can’t afford it,” he said. “So, I watch these kids come in, working two jobs, going to college.”

He pays attention to what they’re going through, much like Steve White, WCU’s former sports information director, did for him when he was playing defensive end and linebacker for the Catamounts. “I really owe Steve White,” Wade said. “He was so instrumental in me getting those two Academic All-American awards.”

While Wade may not have kids of his own, he does in a way — 298 of them for now, and hundreds more once his endowed scholarships kick in. He literally watches over them from his home he built above Rabbit Ridge, a house he sketched on paper more than 40 years ago when he was a college student at WCU.

“I’ve been thinking about doing this for a long time,” he said of his gift to WCU. “I wanted to do something that would outlive me. I think it’s sort of natural for me to give back to the school because it’s where I’m making my money now, in student housing.”

So, what does he want his money to do for WCU? “I want it to go to kids who have this sense of achievement. I want to make sure these kids who didn’t grow up in the same situation that I did have a shot. But I also want them to perform, that’s very important to me as well. You never know what’s going to happen with your gift, except you know it’s going to be given to a student. You don’t know what that student is going to do. You don’t know if the student’s going to cure cancer one day, you have no idea. I think that’s good that we don’t. We just let chance deal with it and that’s OK. We can’t control everything. The only thing I can control is that I can make a gift that will never run out of money, that there will always be a stream of money flowing into the school. And that was a goal of mine.”

For more information, visit LeadTheWay.wcu.edu or call 828-227-7124.