Breaking Barriers

A Pioneer of Integration Recalls the Summer of 1957

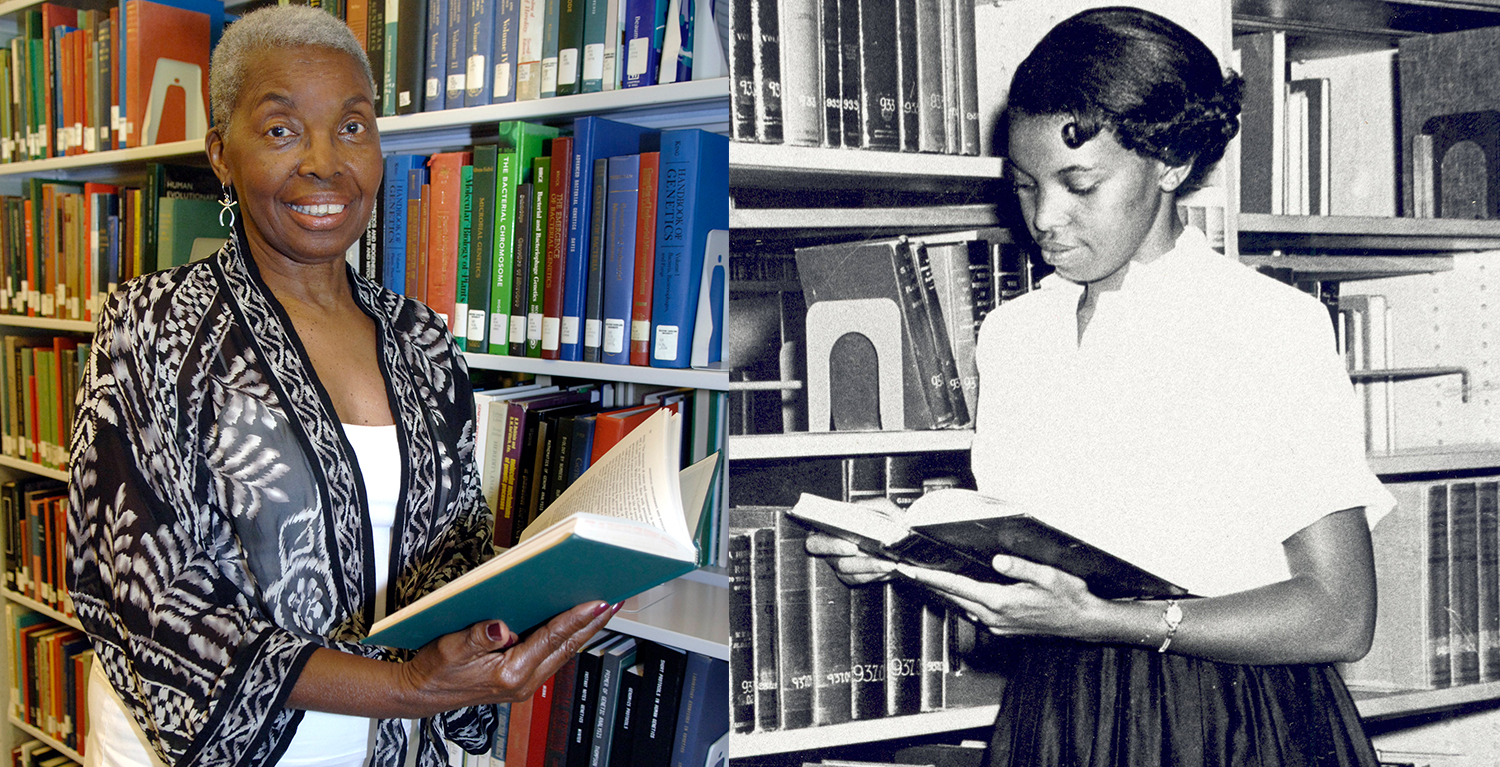

In a return to campus in 2006, Levern Hamlin Allen recreated her 1957 visit to the Hunter Library

The arrival of Levern Hamlin Allen at Western Carolina College on June 11, 1957, did not generate a lot of buzz on campus, despite the fact that the 21-year-old was bringing integration to Cullowhee as the institution's first African-American student. Allen's trek from her hometown of Roanoke, Va., to enroll in a nine-week graduate school summer session was low-key, at most.

"I left home very early and arrived at Western about 3 o'clock in the afternoon," she said. "I was hot, tired, and had cramps in my feet and legs from the long drive, and lots of anxiety. I persevered. I went directly to the office of the director of summer session, registered for three classes, paid my fees and was assigned a room."

And thus Western entered a new era.

Allen had already earned a bachelor's degree in speech correction and English in Virginia and was working as a speech therapist in Charlotte-Mecklenburg schools when she enrolled at Western with the goal of earning nine hours of credit in special education to obtain an advanced North Carolina teaching certificate.

Allen's arrival in Cullowhee came three years after the landmark Brown v. Board of Education Supreme Court decision, which ordered an end to racial segregation in the public schools. All-white Southern colleges were just beginning to receive applications from African-American students. Some schools, including Western, granted admission, but many students won admission only with a court order.

Allen says she found out much later that her first days in Cullowhee were carefully planned to avoid complications. She arrived the day following regular registration, avoiding reporters, and the institution's director of public relations interviewed her and released the story to the press.

"My instructors had been chosen," she said. "They appeared eager to have me as a student. A black family with a daughter about my age called to offer assistance if I needed it. We became friends. They were my lifeline to understanding this new and different culture and a source of comfort."

Overall, the situation remained quiet in Cullowhee. "There might have been some residents who feared change, but it appeared to me that most resigned themselves to the fact that change was coming," she said. "While they did not welcome it with open arms, there was no violence, no fight, no mass resistance.

"When I reflect on that summer, I wonder why," Allen said. "There had been a tremendous amount of violence in several states, and more was to come. However, it never happened in Cullowhee."

Allen went on to earn master's degrees at the University of Maryland and George Washington University. She retired in 1992 after working as a speech pathologist in Washington, D.C.-area schools for 25 years. Currently a resident of Silver Spring, Md., she served Western as a trustee from 1987 through 1995.

Although Allen's 1957 arrival in Cullowhee was quiet, her August 2006 visit to Cullowhee came with a lot of fanfare as the university honored her with an honorary doctorate in humane letters in recognition of her contributions to society as a pioneer of integration and social change, and for her service to the university.

"I always knew that the summer of 1957 was special," Allen said as she accepted the honorary degree at the summer commencement ceremony. "I accept this honor with the love and dignity in which it was presented."

Story by: Randall Holcombe