The People:

Olive Dame Campbell

Olive Dame Campbell’s (1882-1954) role in the Craft Revival was decidedly more academic than that of other mountain workers. Her vision was based on a solid theoretical foundation and articulated in letters, articles, and books. She authored two texts—one on mountain ballads and another on Danish folk schools. She edited her husband’s research notes into a book, and presided over the conference of Southern Mountain Workers after he died. She orchestrated a study of mountain handicrafts and many credit her with envisioning a cooperative marketing guild. In 1925 she founded the John C. Campbell Folk School in Brasstown, North Carolina. Along with Lucy Morgan, she was named a regional delegate to the World Crafts Exposition in 1934.

Olive Dame (1882-1954) was brought up in Medford, Massachusetts where her father was head of a private high school. Three years after graduating from Tufts College in 1903, she met John Charles Campbell, a mission schoolteacher, while onboard a European cruise. Married in 1907, Olive and John Campbell worked together as colleagues, as they lived together as marriage partners. They spent their first year together in a “rose-covered president’s cottage in Demorest [Georgia].” Their lives were “well tuned in serious purpose,” but, like all lives, theirs was not all rosy. During their marriage of twelve years, they had two daughters, both of whom died while still babies. 1

In 1909 John Campbell began receiving a salary from the Russell Sage Foundation. Newly founded in 1907, the Foundation was one of the first in the country to support research into the living conditions of working people. Although Olive was not funded as part of this arrangement, the Foundation did cover her travel expenses. 2 John collected data in preparation of a study on mountain life, while Olive collected mountain ballads. She collaborated with the famed English ballad collector Cecil J. Sharp to co-author English Folk-Songs from the Southern Appalachians, the first songbook to capture traditional melodies along with ballad lyrics. Recorded much later by Library of Congress folklorist Allan Lomax, Olive Campbell can be heard singing the ballad Barbara Allen.

From 1908 until 1913, Olive and John traveled throughout the southern mountains in Kentucky, Tennessee, Georgia, and western North Carolina. They moved from city to city by train, but in rural areas, they went by wagon, horseback, or on foot, depending upon the terrain. Olive Campbell recalled one particularly treacherous visit to the Pine Mountain Settlement School in Harlan County, Kentucky.

[W]e had to walk over Pine Mountain, for the trail was too slippery for horseback. It was a long hard trip for John, climbing up the steep trail in the snow and ice. We took it slowly, with frequent stops to admire the beauty of the woods, and to catch our breath.

A friend recalled their differences:

Mr. Campbell arrived gray with fatigue and cold, exhausted by the pain of angina attacks he had suffered on the journey. His wife, despite her anxiety for him, was fresh and rosy from the frost. 3

In 1909 Olive and John Campbell attended the Southern Education Conference in Atlanta along with Russell Sage director John Glenn and his wife. A handful of “mountain workers” attended an invitation-only “parlor conference” to talk about problems particular to mountain communities. Olive Campbell recalled this gathering as a “forerunner” of the Council of Southern Mountain Workers established a few years later. In 1913 the Council began holding annual conferences, enabling those workers in the “mountain field” to meet and strategize in an “exchange of ideas to further the best methods of work.” Held each April in Knoxville, Tennessee, the conference hosted presentations and roundtable discussions on topics of mutual interest. Thirty people came to the first conference in 1913, but by 1918, there were more than 150 in attendance. Leaving the Knoxville conference in 1913, John and Olive moved to Asheville to open the Southern Highland Division of the Russell Sage Foundation. 4

The Campbells were introduced to the concept of the Danish folk school by P. P. Claxton, a member of the Southern Education Board who later became United States Commissioner of Education. After democratic revolutions gave voting rights to a mostly unlettered population, Denmark developed a nationwide system of schools “for the purpose of making good citizens” of her people. The folkehojskoler—translated from the Danish as “folk school”—placed less value on “exact knowledge for its own sake,”focusing instead on critical thinking and vocational skills. Olive Campbell described its purposes in idealistic terms: “to awaken, enliven, enlighten — awaken to new ideas, new ideals; keep purposes alive and in action…to the good of community, country, mankind.” 5 Olive and John had shipboard tickets for Denmark when World War I broke out in Europe. Postponing their trip, John Campbell never saw Denmark. He died in 1919.

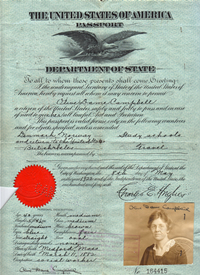

Olive Campbell closed the Southern Highland Division office in Asheville and sequestered herself in Massachusetts for the next two years. Working from her summer home in Nantucket and her childhood home in Medford, Campbell compiled, organized, and edited her husband’s notes. According to Edith Canterbury, the project’s secretary, John had written the preface and first chapter of the book. “Out of the multitude of papers, letters, and bits of writing,” Olive Campbell wrote, attempting to emulate John’s writing style. The finished study—The Southern Highlander and His Homeland—was published in 1921, under his name. In the spring of 1922, with a fellowship from the American-Scandinavian Foundation, Olive Campbell set sail for Copenhagen. Accompanied by her sister, Daisy Dame and colleague Marguerite Butler, a teacher at the Pine Mountain Settlement School in Kentucky, the trio traveled to Denmark, Norway, Sweden, and Finland. The three women spent 18 months in Scandinavia, often traveling by bicycle, described by Marguerite Butler as an “intimate way to see and know the country.” 6

In 1925, with the help of Marguerite Butler, Campbell looked for a location to establish her own folk school. From the privacy of her room at the Hotel Regal in Murphy, North Carolina, she wrote to a prominent member of the Brasstown community about the formation of a rural folk school, calling it “our particular experiment.” Comparing her idea of a mountain school to the schools she visited in Denmark, she wrote,

Breaking away from grades and credits, [they] have sought to relate the culture of books to the culture of the soil, which have put personality and its influence above the accumulation of facts, and the work of every day above mere academic learning. 7

The letter reveals the clarity of her vision. “We expect to have a little log museum,” she wrote. Indeed, one was built the following year.

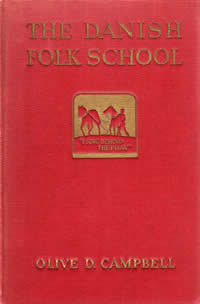

Campbell continued to hone her vision and articulate her aims. She often posed a key question—“How shall we keep an enlightened, progressive, and contented farming population on the land?”—and answered it by creating the John C. Campbell Folk School. Founded in 1925 and named in honor of her husband, the school’s initial programs were broader than those of other mountain schools. Agriculture and related activities—a banking cooperative and a creamery—were among its earliest endeavors. In 1928, completing her study of schools visited in Scandinavia, Campbell wrote The Danish Folk School. She attributed the philosophy of the folk school to the reformer and historian Grundtvig. Paraphrasing Grundtvig, she wrote,

In 1935 this image was recorded with the U.S. Copyright Office as the John C. Campbell Folk School logo

In 1935 this image was recorded with the U.S. Copyright Office as the John C. Campbell Folk School logoThe humble tasks of farm, shop and home have a cultural value more fundamental than that of books. Education should not discredit such labor but should give meaning breadth and depth. It should link culture of toil and culture of books….It should be enlightened action.

Maintaining a focus on the land, a farmer with a team of workhorses is pictured on the book’s cover. This same motif was later adopted as the school logo, inscribed with the motto, “I sing behind the plow.” 8

Folksong scholar Cecil Sharp described Olive Dame Campbell as having “the combination of scientific and artistic spirit which work of this kind needs if it is to be of any use to posterity,” traits that ensured the successful operation of a school. Sharp’s assessment of Campbell’s personality proved accurate; the programs she put into motion continue 80 years later. Always a strategic thinker, Campbell was also a natural-born teacher.

Olive Campbell was at her best in informal meetings with her students, perhaps before the open fire with a group or with one or two alone wherever chance brought them together. Questions and comments were exchanged.

The Folk School centered on developing a sense of community, placing personal interaction as a core value. “In a true folk school students and teachers live together as a family,” noted a school newsletter. 9

Initially the John C. Campbell Folk School was not focused on crafts. Instead, the curriculum was broad based to include forestry instruction, travel, history, public health, mechanical drawing, and a wide variety of agricultural subjects. Under the heading of “New Interests and New Industries,” the John C. Campbell Folk School newsletter reported on “Handwork Week,” an event held in August 1928. Women brought their spinning and carded wool. The 1928 school newsletter includes a picture of students weaving, the first time an image of handwork appeared in a school newsletter. 10

In 1929 the John C. Campbell Folk School formed a Handicraft Association of community makers who produced hearth brooms, quilts, benches, and baskets. While the school experimented with weaving early on, Campbell believed that the market was “overstocked with handmade cloth.” Consequently, the Folk School turned to woodcarving after Campbell noticed local men whittling, a traditional pastime.

Her eyes were ever open to new opportunities; witness the now famous bench which then stood on the store porch and on which the menfolk whittled while they settled the affairs of the world. It seemed a pity to Olive Campbell that men long skilled in the use of the pocketknife should not use it creatively. 11

Always ready to try new things, Olive Campbell learned to carve.

Following the model of Berea College’s turn-of-the-century “fireside industries,” the school connected to the surrounding community through local craft. The John C. Campbell Folk School organized the Brasstown Carvers, a community group similar to those affiliated with other Craft Revival centers. Allanstand Cottage Industries operated out of the Presbyterian Home Mission and the Penland Weavers and Potters was supported by the Appalachian School. Although craft work was not the main thrust of the folk school at the time of its founding, it continued to play an important role. Drama, song, and dance were equally valued. Curiously, Campbell used craft as a metaphor in an early description of the school, before crafts were actually taught.

We listen to sound of hammer, saw and plane in the carpentry room, to the thud of the loom and whirr of spinning wheel in the weaving and sewing room; we watch them at their daily physical training in the gymnasium; we hear them singing--for it is song that welds the group. 12

Olive Campbell continued to preside over the conference of Southern Mountain Workers. In 1926 Campbell invited Allen Eaton to present and in 1927 Edward Worst was a guest speaker. Both men were considered leading experts on American craft at the time. Conference sessions on mountain handicrafts allowed interested participants to develop and share ideas. In December 1928, Campbell was one of seven Craft Revival promoters who met to discuss the formation of a cooperative guild. Some credit her with initiating the idea. Weaver and shop owner Clementine Douglas wrote, “The germ of the idea for a cooperative organization for the mountain crafts sprang to life in the mind of Olive Campbell.” Lucy Morgan, organizer of the Penland Weavers and Potters, concurred. She wrote that Campbell “asked some of us who were craft-minded to think with her about the possible values of forming a handicraft guild.” Period documents support this claim as well. In a letter to John Glenn, Olive Campbell articulated the need for a “loose federation” of craft producers as early as 1928. Always one to dig deeper into the philosophical underpinning of activity, Campbell asked,

Is there, or is there not a connection between the type of work represented by these crafts and the program for social improvement, which all of the schools really have at heart, however blindly they go about it? And if there is a connection, what is it and how is it related to the matter of perfection of output and economic return? 13

A core group of craft enthusiasts continued to meet to develop the idea of a cooperative guild. In 1930, at the annual Knoxville conference, they formally organized the Southern Mountain Handicraft Guild, today’s Southern Highland Craft Guild.

In 1928 Olive Campbell wrote to John Glenn to propose that the Russell Sage Foundation support a study of mountain handicrafts similar to the one her husband did on mountain life. She went a step further, making a case for Allen Eaton to conduct it, noting his ability to gain the “confidence of the people.” Working on a study that covered 235 counties in five states, Eaton depended on Campbell for guidance. After arranging for photographer Doris Ulmann to take pictures for the book, Eaton wrote to Campbell requesting her help in identifying appropriate subjects and craftsmen. “Ask Marguerite,” he wrote, “to put down in pencil…every good subject, person, or scene, and the place where it is.” Doris Ulmann was soon a regular visitor to the folk school and the two women formed a close friendship. After one of her first visits to the folk school, Ulmann wrote, “These interesting busy weeks will always remain a landmark in my life and it is such a precious possession to know you.” These words were more prophetic than she realized; Doris Ulmann lived but one more year. That next summer Ulmann wrote to her friend and colleague, “As usual, the trouble about visiting you is leaving you.” Ulmann’s images, many of them taken in Brasstown, were published posthumously in Eaton’s Handicrafts of the Southern Highlands in 1937. 14

Olive Dame Campbell touched the lives of many involved with the Craft Revival. When she died in 1954, Mountain Life & Work, the “magazine of the Southern Mountains,” dedicated an entire issue to her as a memorial. Allen Eaton recalled “a hundred memory pictures of Olive Campbell.” Others wrote testimonials. Olive Campbell’s “Living Words” retain their meaning today in rural communities struggling with issues of environmental degradation and job creation. She wrote,

How many of us who talk of rural problems and rural life, really believe in the country? We speak of the fine independence of farm life but deep down in our hearts do we not still measure success in urban terms of reputation, money, freedom from manual labor? 15

- M. Anna Fariello, 2007

See More: Writings and Carvings by Olive Campbell

1. Biographical information from “Mrs. John Campbell,” Southern Mountain Life and Work (April 1925): 6 and included in a letter from John C. Campbell to John Glenn, May 15, 1908 reprinted in Olive Dame Campbell, The Life and Work of John Charles Campbell (Madison, Wisconsin: Privately printed, 1968) 110-111. Edith Canterbury, “Background Years,” Mountain Life & Work 4 (1954) 8. Edith Canterbury was John Campbell’s secretary and, after his death, assisted Olive Campbell in writing his study.

2. John Glenn to John C. Campbell, July 12, 1909. The Russell Sage Foundation paid John Campbell an annual salary of $2,500 per year plus all expenses for both of them.

3. Olive Dame Campbell, 559. Canterbury, 6.

4. Olive Dame Campbell 198, 266, 334. Canterbury, 9-10.

5. P. P. Claxton to John C. Campbell, Jan. 2, 1911 reprinted in Olive Dame Campbell, 228 and 205. “Philander Priestly Claxton,” Tennessee Encyclopedia of History and Culture at http://tennesseeencyclopedia.net. American Consulate General, Copenhagen to John C. Campbell, April 30 [1911] reprinted in Olive Dame Campbell, 205-206. Later, in a Feb. 26, 1931 letter to Claxton, Campbell wrote, “Do remember that Mr. Campbell had his first knowledge of the folk school from you.”

6. Canterbury, 11-13. Marguerite Butler Bidstrip, “To Denmark,” Mountain Life & Work 4 (1954): 14. While Olive Campbell closed up the house that served as the Russell Sage headquarters, she continued to receive support from the foundation until 1928. With support of the foundation, she completed John Campbell’s study and presided over the Council of Southern Mountain Workers.

7. Olive Dame Campbell to Dr. James H. Dillard, November 24, 1925 in John C. Campbell Folk School Archives.

8. Olive Campbell posed this question numerous times, in the introduction to her book The Danish Folk School: Its Influence in the Life of Denmark and the North (New York: Macmillan, 1928), page vii, and again in the April 1928 John C. Campbell Folk School newsletter. Grundtvig philosophy from Olive D. Campbell, The Theory of the Danish Folk High School (privately printed pamphlet, circa 1924). Letter from John C. Campbell Folk School Secretary to Copyright Office, March 21, 1935 in John C. Campbell Folk School Archives.

9. Cecil Sharp quoted in Mountain Life & Work 4 (1954) 18. Louise Pitman, “The Living Word,” Mountain Life & Work 4 (1954): 20; Pitman spent 17 years teaching at the Campbell Folk School. John C. Campbell Folk School 3 [school newsletter] (April 1927).

10. John C. Campbell Folk School 5 [school newsletter] (April 1928).

11. John C. Campbell Folk School 8 [school newsletter] (Nov 1929). Olive Dame Campbell to John Glenn, March 7, 1928. Pitman, 21.

12. Olive Dame Campbell, “Report of the John C. Campbell Folk School,” Southern Mountain Life and Work (July 1926): 27.

13. Lucy Morgan with LeGette Blythe, Gift from the Hills: Miss Lucy Morgan’s Story of her Unique Penland School, 2nd ed.(Indianapolis: Bobbs Merrill, 1958), 78. Clementine Douglas, “Crafts for all the People,” Mountain Life & Work 4 (1954): 31. Olive Dame Campbell to John Glenn, March 7, 1928.

14. Olive Dame Campbell to John Glenn, March 7, 1928; in this letter Campbell put forth two names: Allen Eaton and Edward Worst but suggested that Worst “was not able to get close to the people” as Eaton had. Doris Ulmann to Olive Dame Campbell, August 7, 1933; Allen Eaton to Olive Dame Campbell, July 13, 1933; in John C. Campbell Folk School Archives.

15. Olive Dame Campbell, "Flame of a New Future for the Highlands," Southern Mountain Life and Work 1 (April 1925): 12.