The People:

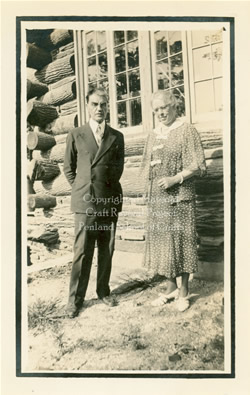

Edward Worst

Edward Francis Worst (1866-1949) was a Chicago educator and pioneer in the manual education movement in the United States. He wrote four books within twenty years, which brought him to the attention of Craft Revival leaders in western North Carolina. His first visit to the region, to participate in the Conference of Southern Mountain Workers in 1927, began a relationship that would last a lifetime. Worst taught an annual summer weaving institute in Penland, North Carolina beginning in August 1928 and returned every summer until his death in 1949. The Penland community honored his voluntary service by constructing a studio in his honor. The Edward F. Worst Craft House continues to serve today’s Penland School of Crafts.

Born in 1866, Edward Francis Worst was raised in Illinois. He went to Illinois Normal College and Cook County Normal School, earning a teaching certificate. As a teacher, Worst introduced crafts into his classroom teaching. Like others in the Progressive Education movement, his interest in handwork was its relationship to other disciplines. For Worst and others, manual training was not vocational; instead, the manual arts were taught to young children to help develop mental acuity. Worst’s book Construction Work: Its Relation to Number, Literature, and History, and Nature Work illustrated this idea. In this text, handwork—what Worst called “construction work”—could inform other academic disciplines including mathematics (“number”), literature, history, and science (“nature work”). Worst outlined exercises for elementary students to teach counting and measuring. Students made paper baskets and other simple objects.

The Chicago Manual Training School was founded in 1883, the first of a handful of manual training programs that operated in Chicago during the last decades of the nineteenth century. An idea that quickly gained support, by 1905 there were over one hundred such schools. 1 All over the US, “industrial schools” and “industrial institutes” were founded to teach students of limited means and provide a more educated workforce for American industry. In western North Carolina, one such school was the Appalachian Industrial School, founded in 1913 in the community of Penland. In 1914 the school added spinning and weaving as an option for girls.

In many parts of the country, manual or industrial arts was taught in local schools. Typical courses included clay modeling, wood construction, leather working, metalworking, and weaving. Before there were any schools known as “craft schools,” manual arts programs operated in a variety of educational venues. Programs served different types of students in technical, commercial, trade, manual, and industrial institutes and schools. In spite of their different names, all manual arts programs emphasized handwork, sharing a goal to reverse “the divorce between the hand and the brain.” 2 These schools operated with a broadened curriculum, designed to keep young people in school and provide them with a skill. They were the precursor to today’s vocational education programs.

In 1900 Edward Worst was appointed principal of the Yale elementary school, a training ground for student teachers of the Chicago Normal School. In 1904 he developed the “Normal Extension” program at Chicago Normal, where he taught paper and cardboard construction, metalwork, woodwork, basketry, and weaving. Within a few years he added an advanced thirty-week weaving course for teachers. Encouraged to expand the weaving program by the school administration, Worst attended the Lowell Textile School in Lowell, Massachusetts, an American industrial weaving center. Worst’s courses for teachers were extensive and hands-on to the extreme. A course in linen production taught in 1907 began with the cultivation of a flax field. Worst was one of the first educators to consider the therapeutic value of handcraft. He taught occupational and physical therapy skills to employees of state mental institutions and pioneered one of the earliest occupational therapy classes in Illinois. In 1915 he began instructing teachers of mentally and physically handicapped children in Chicago Public Schools. 3

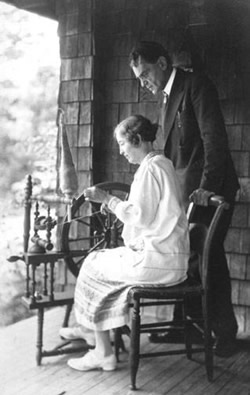

To learn more about manual arts programs, Worst and his wife Evangeline, traveled to Europe to study handicrafts schools. Worst was inspired by visits to Norway and Sweden, where “hand loom weaving [was] a very successful line of home industry.” Sometime between 1910 and 1914 Worst purchased spinning wheels and looms and had them shipped from Sweden to Lockport, Illinois where he organized Swedish immigrants into a cottage industry. Originally named the Lockport Home Industry, the group changed their name to Lockport Cottage Industries in 1923. In Appalachia, similar cottage industries were developed as part of the Craft Revival. These, however, tended to use unskilled labor in programs that were both economic and educational. Lockport Cottage Industries, however, did not propose to teach weaving to the uninitiated. Instead, Worst organized already skilled Scandinavian weavers into a commercial enterprise. 4

Through the publication of his books, Edward Worst became a national expert on weaving. Foot-Power Loom Weaving, published in 1918, described the weaving process in detail. The text explained the complicated mechanics of warping a loom and the use of a draft in the development of a weaving pattern. The next year Worst wrote Industrial Work for the Middle Grades, and in 1926, a text on How to Weave Linens. By 1926 Edward Worst was America’s foremost authority on hand weaving. Meanwhile in western North Carolina, Lucy Morgan, a teacher at the Appalachian School (formerly the Appalachian Industrial School) traveled to Kentucky to study weaving during her nine-week mid-winter vacation. She studied at Berea College’s Fireside Industries, a well-established program that had weaving as its primary focus. It was here that Morgan first learned of Worst, having been introduced to his book by her weaving teacher. 5

Returning to the Appalachian School, Morgan invited neighborhood women to a demonstration. In the fall of 1923, Morgan brought a loom to the home of Martha Adeline Willis and spent three days with her setting it up. Ordering a dozen more Swedish-style looms from Berea, Morgan organized local women into a weaving cooperative. She provided looms and materials to local women and sold their products at resort hotels. Morgan was inspired to “bring about a revival of hand-weaving” and “provide our neighbor mothers with a means of adding to their generally meager incomes.” The Appalachian School accommodated her, naming her director of a new Fireside Industries program. 6

The activities of Morgan were typical of the Craft Revival; educators worked hand-in-hand with local citizens to produce work for sale and establish cottage industries in the mountains. In the 1920s Craft Revival leaders were just coming to know one another. There were no guilds or organized events, except for the annual Conference of Southern Mountain Workers held each spring in Knoxville, Tennessee. At the time, the conference focused on a variety of issues and attracted a diverse audience of “mountain workers,” from religious programs, settlement schools, and cottage industries. In the mid 1920s, the “handicraft” contingent was emerging with programs focused on craft production and marketing.

In March 1927 Edward Worst came south from Chicago to Knoxville as a guest of the Conference of Southern Mountain Workers. He presented a program on “Handwork for the School and Home” and presided over a roundtable on “Fireside Industries.” Worst’s role at this session was one of critique. An exhibit of crafts had been set up and Worst examined each piece, making recommendations for improvement to each production center. At the conference,

“Someone suggested a summer school where those already possessing a general knowledge of weaving might get new ideas and learn more of the possibilities of foot-power looms, not yet used by the mountain workers. 7

The idea apparently caught Lucy Morgan’s attention because, the following summer, in August 1928, Worst came to Penland for the first time.

In a three-day session, Edward Worst set up a multiple-harness loom and taught weaving to local women on the campus of the Appalachian School. In the fall, after Worst sent a Chicago potter to Penland to help establish a pottery program there, the Penland Weavers and Potters were formally organized, replacing the school-affiliated Fireside Industries program. Lucy Morgan was quick to recognize the expertise that Worst brought to her project. Her enthusiasm was unbounded, “It was manna from heaven,” she later wrote. In the winter months following the first weaving institute in 1928, Morgan spent nine weeks in Chicago working in Worst’s studio every day. Worst commented on her aptitude, “She is quick to take new suggestions,” he wrote in a letter. 8

Although she was raised in the mountains of western North Carolina herself, Lucy Morgan had a way of connecting with people that helped propel Penland onto a national, if not international, stage. She was not intimidated by difference and, in fact, seemed to relish in cultural contradiction. Morgan expressed “great satisfaction” at

“Seeing Mr. Edward F. Worst of Chicago—North Shore Drive, Art Institute, Marshall Field, Al Capone, stockyards, political conventions, booming business, roaring traffic—happily engrossed in the exchange of ideas and techniques with Aunt Cumi Woody, who dressed in a basque and full skirt, parted her hair in the middle and combed it sternly into a bun at the back of her neck. It always seemed mighty American.” 9

Lucy Morgan had planned the first summer weaving institute as something for her “neighbor mothers,” local women who participated in the school’s Fireside Industries program. She had no way of knowing that Edward’s Worst’s visit would draw the attention of Paul Bernat, owner of Bernat & Sons textile supply company and publisher of The Handicrafter magazine. In the next issue, Bernat wrote about Worst’s workshop. Letters came in from all parts of the country as a result of the national publicity. The next summer, seven women each paid a dollar a day for room, board, and tuition. Morgan noted the connection between Penland’s future and Edward Worst’s teaching.

“It was in August 1929 then, that I consider the Penland School of Handicrafts was born. That was the year we had our first outside students.” 10

In spite of the fact that the country was in the midst of the Great Depression, the summer Weaving Institutes attracted students. In 1931 there were forty students from fifteen different states. Most were professionals, including teachers, doctors, and nurses; one third were occupational therapists, no doubt due to Worst’s reputation in this area. In 1933 the Weaving Institute was expanded to include a preliminary week of instruction aimed at local women. This included “thorough training in the mechanism of the loom, setting up the loom, warping, beaming, threading, and weaving simple designs,” prerequisite skills for Worst’s regular session. 11

By 1932 enrollment in the Weaving Institutes was limited by the school’s facilities. The need for more space was becoming obvious. Morgan conceived of an instructional studio, a “mansion in the sky,” and borrowed “all the money they would let me have” to finance its construction. A new workshop was a monumental undertaking, one that was paid for piece by piece. Students attending the 1934 Weaving Institute sold subscriptions: $1.00 bought a membership fee, $2.50 bought a log. Finally, there were enough pledges and enough funds to move forward and in May 1935 construction began. An announcement proclaimed the “Log Raising” for a “a workshop, a national laboratory for weaving” that would be named the Edward F. Worst Craft House. 12

In her memoir Lucy Morgan described the “log raising.

The work of the day began. The four notchers took their places, one at each corner of the building. Neighbors hitched their teams…and snaked the logs [into place]….Notchers measured and notched, mules strained and pulled, men with axe and saws worked and sweated.

The noon meal was a community event.

The mules were fed and watered; and the men, women, children and babies gathered under the trees…For miles around the women had come in with hams baked to a delicious tenderness, fried chicken, sausages, vegetable of every sort, jellies, jams, pies, pickles and cakes…

Morgan’s narrative concluded,

By nightfall the four walls of the Edward F. Worst Craft House were standing…the day before Mr. Worst returned in August the last nail went into the roof.

Former Weaving Institute students gave the furnishings for the front room, dubbed the “Chicago Room.” The four-story 50 x 80 foot studio remains part of today’s Penland School of Crafts. 13

Worst expanded the school’s program by offering its first-ever first spring session in April 1936. That year he taught two sessions, his usual summer weaving institute in August and the earlier one in the spring. He was assisted by Rupert Peters, who came to Penland the previous summer as a student. By 1936 the summer sessions were hosting over 100 students. Edward Worst returned to teach at Penland every summer until his death in 1949. 14

- M. Anna Fariello, 2007

1. Olivia Mahoney. Edward F. Worst (Chicago, Chicago Historical Society, 1985), 14, 31. Mahoney explains, “Manual training remained an important part of Chicago’s public school curriculum through the 1920s and into the early 1930s, but its primary source of support shifted from educational reform theorists to vocational training advocates who stressed practical skills.”

2. Oscar Lowell Triggs, “School of Industrial Art,” The Craftsman II, No. 4 (January 1903): 216. The manual arts enjoyed a place in the Progressive Education movement, which attempted to place education at the core of society. Specific objectives aimed at keeping students in school, teaching skills that related to a student’s environment, and creating a democratic society.

3. Mahoney, 14-19, 39. Mahoney gives credit to Worst’s supervisor, Ella Flagg Young, principal of Chicago Normal and an associate of John Dewey.

4. Mahoney 18-19

5. Bonnie Willis Ford, The Story of the Penland Weavers (privately printed, 1934 edition) unpaginated. Bonnie Ford relates that Morgan was introduced to Worst’s book by her Berea weaving teacher, presumably Anna Ernberg.

6. Lucy Morgan with LeGette Blythe, Gift from the Hills: Miss Lucy Morgan’s Story of her Unique Penland School (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1971 original Bobbs Merrill, 1958) 50. Appalachian School catalogs from circa 1924 to 1929 carry Lucy Morgan’s name as “Director of Fireside Industries.”

7. “Evening Session—March 30, 1927,” Mountain Life and Work (July 1927): 21-22. Other topics covered in this issue of the magazine included: “Round Table Discussions,” 23-24; “Fireside Industries,” 26; and “Exhibits at the Conference of Mountain Workers,” 27-28. The Southern Mountain Workers conference was initiated in 1913 by John Campbell and presided over by his widow Olive Campbell after his death in 1919. Olive influenced its direction, bringing Allen Eaton to the conference in 1926. Conference proceedings were often chronicled in the periodical Mountain Life and Work.

8. Morgan, 86. Letter from Edward F. Worst to Mr. Taylor, Feb. 28, 1929, Berea College Archives. This letter also comments that (Howard) Tony Ford had also been to Chicago, probably to help Morgan settle in. Ford, formerly of Penland, was at Berea College as part of an enterprise referred to as the “Mountain Weaver Boys.” In her memoir, Lucy Morgan never mentions the nine weeks she spent in Chicago, but it is noted in Mahoney, 34. Ford’s Story, written five years after the fact, dates Morgan’s nine-week stay in Chicago before Worst’s first visit to the region and credits Morgan with inviting Worst to the Conference of Southern Mountain Workers. My interpretation relies on Worst’s first person letter, which places Morgan’s visit after the first weaving institute at Penland. I believe that Morgan first met Worst at the 1927 conference and followed up on the suggestion to host a “summer school.”

9. Morgan 87.

10. Morgan, 96-97. Linda Darty, “The Dream of Miss Lucy Morgan,” American Craft 41 (Oct./Nov. 1981): 2-3.

11. “Fifth Annual Weaving Institute at Penland,” [Supplement to the] Handicrafter, circa 1932, unpaginated.

12. Morgan 101. Ford, 1934. “Log Raising for the Edward F. Worst Craft House,” (Penland, North Carolina, 1934) Archives of American Art (#4515).

13. Morgan, 103-109, 115.

14. Ford, 1934. Morgan, 123-124. “Ninth Annual Weaving Institute,” (Penland, North Carolina, 1938).