History project is helping inform a documentary on endangered right whales

By Tom Lotshaw

A North Atlantic right whale and calf. Photo courtesy of NOAA Fisheries.

When Vicki Szabo, associate professor of history, finished her 2008 book on medieval whaling, she quipped in the acknowledgements she would remember all her Western Carolina University colleagues when it was made into a feature film.

Szabo’s new project about Vikings and marine mammals is coming a little closer to the movie screen. She spent part of fall semester in Iceland working on an upcoming documentary about critically-endangered North Atlantic right whales.

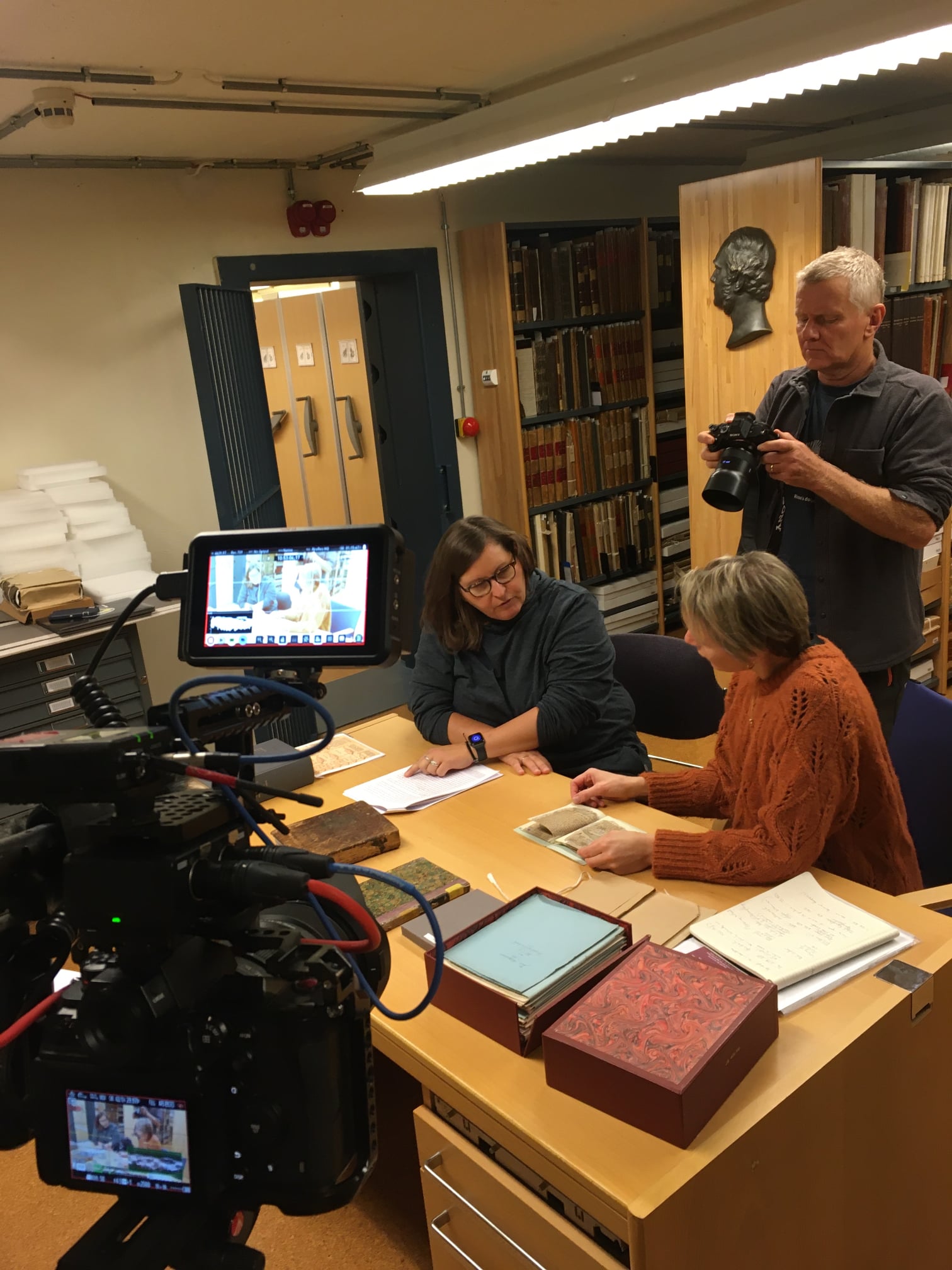

Vicki Szabo, left, Emily Lethbridge, of the Árni Magnússon Institute for Icelandic Studies, right, and Nick Dean, of Spindrift Images, review Norse manuscripts in the Icelandic National Archive in Reykjavík.

The project explores how the seafaring Norse utilized whales, seals and walruses over 1,000 years, from 800 to about 1800. The timeframe spans Viking voyages to Iceland, Greenland and North America, and the onset of the Little Ice Age, a centuries-long cooling period for parts of Earth.

More than a dozen researchers from seven countries are working on the National Science Foundation project. The interdisciplinary team includes archaeologists, folklorists, biologists, molecular scientists and historians like Szabo. It also has employed eight WCU students from various programs.

The researchers have been translating and investigating Norse texts, examining archaeological sites and artifacts from Iceland and Scotland and analyzing unearthed animal bones with DNA and other advanced tests. Their goal is to learn more about the Viking age and marine mammal populations of ancient northern seas — knowledge that could help inform modern-day ocean conservation efforts.

The project caught the attention of Spindrift Images, a husband-and-wife team working on a documentary exploring the plight of North Atlantic right whales and what can be done to avert their human-caused extinction.

Commercial whalers hunted the right whale species nearly to extinction by the 1890s and eradicated it from European waters centuries earlier.

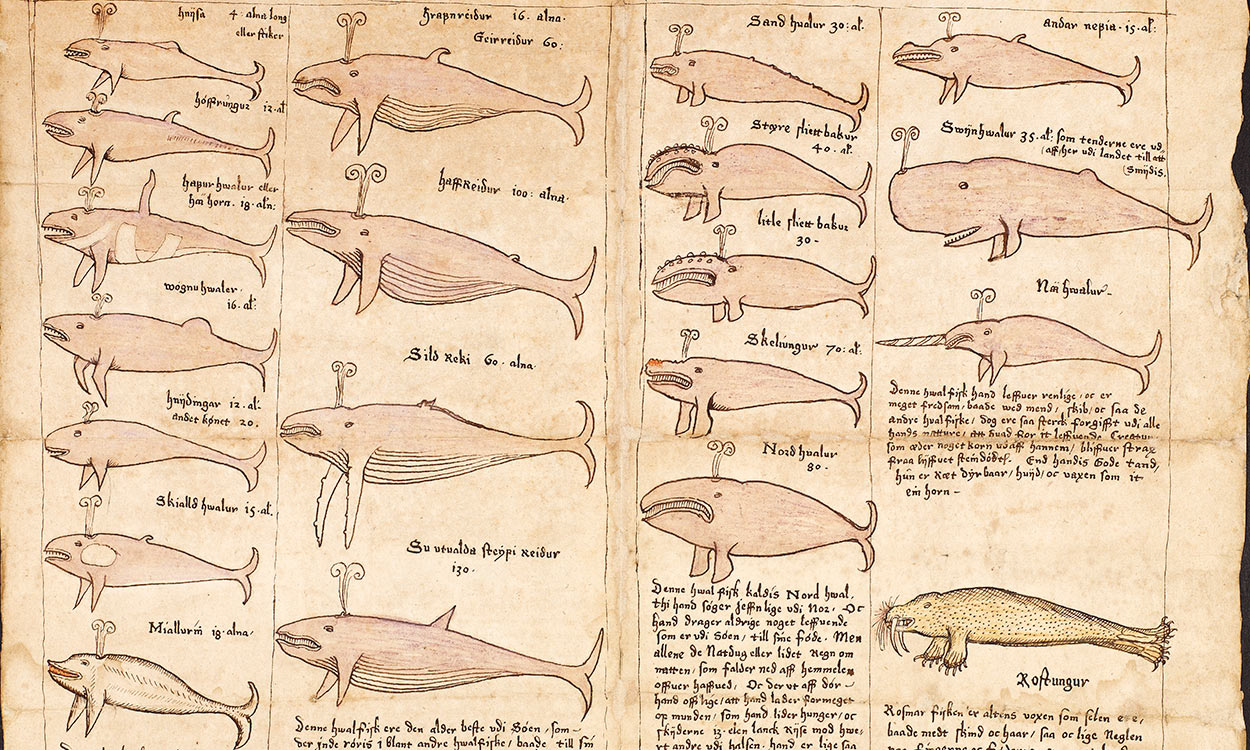

An illustration of whale species created by Jón Laerði, or Jon the Learned (1574-1658), from his “Natural History of Iceland,” GKS 1639 kvart, Royal Library, Copenhagen. Photo courtesy of Icelandic Museum of Natural History.

The whales, which grow up to 52 feet long and weigh up to 140,000 pounds, remain imperiled today. They are at risk of deadly vessel strikes and fishing gear entanglements as they migrate along North America’s busy eastern seaboard, and also face threats from ocean noise pollution and climate change. Biologists estimate fewer than 350 are left, with less than 95 reproductive-age females.

Szabo’s project is documenting some of the earliest human impacts on North Atlantic right whales, making it a natural starting point for the documentary. She and some research partners met the Spindrift Images team at Iceland’s national archives in Reykjavík and then traveled with them to a site in the country’s far north, just below the Arctic Circle, to share their findings.

Jane Eastman (left), with WCU’s Anthropology Department, and Alex Macaulay, with WCU’s History Department, helped Szabo butcher a pilot whale that washed ashore dead on North Carolina’s Outer Banks.

“The work Vicki and her colleagues are doing is fascinating, giving us a glimpse of how the Norse hunted whales,” said Cheryl Dean, of Spindrift Images. “It will be great to be able to include this part of history in our film to show that right whales have been struggling to coexist with people for centuries longer than most people realize.”

Now in its sixth and final year, the project is revealing that the medieval Norse were more knowledgeable about different whale species than previously thought. They were hunting some species, including the right whale, and observing and reacting to changes in their populations.

“I think we’re discovering and telling this new story about how people in the past were aware that the seas were changing and that they were losing whales,” Szabo said. “I think they were not entirely sure why. But they knew they were making an impact, which is fairly disturbing in that early of a stage.”

There is evidence of Norse whale hunting as early as the 800s.

Unlike devastating commercial whaling centuries later, Norse whale hunting is believed to have been almost entirely opportunistic, though ancient texts highlight its importance. One whale could provide thousands of pounds of meat that could mean the difference between survival and starvation for entire settlements in the harsh North Atlantic. The whales’ bones provided a versatile material for tools, goods, even buildings.

This image shows sea monsters of the North Atlantic as depicted by Olaus Magnus in Carta Marina, 1539.

Norse laws prescribed how whales were to be butchered and set harsh punishments for theft, including outlawry. They allocated the largest shares to the hunters who mortally wounded a whale, identified by registered marks on their hunting weapons. Smaller shares were reserved for the people who later found the dead whale or owned land where it washed ashore.

Even the limited hunting could have impacted whale populations, including the North Atlantic right whale, Szabo said. Medieval hunters targeted migrating whale calves, a strategy that doomed small populations, particularly during a time of stressful climate change like the Little Ice Age.

Szabo’s project is also working to connect those lost whale populations with the right whale populations of today by comparing the genetics of remains found at Norse sites with modern whales. That research by Brenna Frasier, of Saint Mary’s University in Nova Scotia, aims to shine more light on the endangered right whale species, its former distribution and genetic diversity, and how the whales may have lost the “migration memories” that might otherwise help them recolonize once-perilous waters off Europe.

Another finding the researchers are working to understand is the number of blue whale bones discovered at Norse sites.

Vicki Szabo studies an artifact made from a fin whale vertebra. It was recovered from a late Iron Age archaeological site at The Cairns in Orkney, Scotland.

In sagas, the Norse claim to be hunting the massive blue whale, which grows up to 110 feet long and weighs up to 330,000 pounds, prizing it as their whale of choice. Researchers have doubted the claim, Szabo said. That’s largely because of the blue whale’s size, speed and preference for offshore waters. But it’s also because blue whales tend to sink when killed, unlike North Atlantic right whales, which tend to float because of their higher blubber content.

Yet, DNA testing for the project has found blue whales to be the most abundant whale species found throughout all the Norse sites. “So now we have this great mystery to try to figure out,” Szabo said.

Szabo specializes in medieval environmental history and has studied medieval whaling and whale bone artifacts for two decades. She describes this project as a “dream come true” and “incredible challenge.”

The project has taken Szabo to countries across the North Atlantic for research and collaboration. It also unexpectedly took her to North Carolina’s Outer Banks. There, in a buggy marsh on a muggy May morning last year, she and WCU colleagues Jane Eastman and Alex Macaulay butchered a 12-foot pilot whale that washed ashore dead. The surprise research opportunity gave them a chance to experience firsthand how the medieval Norse would have processed a whale.

History is about more than the archives, Szabo said. Like many research initiatives in WCU’s history department, this project is trying to use every available resource to piece together a better understanding of the past and its importance for the present and future. Szabo hopes it will help encourage WCU students to take creative approaches in their own studies of the past.

“We’re working with documentary filmmakers on the preservation of a whale species. We’re learning how whales are put together and how whales come apart. We’re learning how to work whale bone and how medieval people worked whale bone. And we’re trying to relate all of this with the stories the Norse told about using whales in the past,” Szabo said. “It’s a completely holistic project using every tool at our disposal.”