Monarch butterfly migration aided by native plants on WCU campus, Highlands Biological Station

The North Carolina mountains are a corridor along the “Butterfly Highway,” an annual migration route of monarch butterflies from the eastern United States and Canada to Mexico, with Western Carolina University a frequent stop along the way.

“The monarchs are on the move already through our area - and will increase in numbers over the next several weeks,” said Jim Costa, executive director of WCU’s Highlands Biological Station and professor of evolutionary biology. Every fall, monarchs will cover thousands of miles to warmer climes for the winter, he said. The distinctive butterflies, with orange wings edged in black dotted by white spots, travel to locations they haven’t visited in their lifetimes.

After the young of an overwintering population matures in a small, mountainous area of Michoacan, Mexico, northern migrations begin in the spring and summer. The trip to the U.S and Canada, unlike the fall migration, will take several generations to complete. Vital for monarch survival and multigenerational development is the milkweed, a perennial often eradicated from lawns and gardens.

WCU, however, has areas across the Cullowhee campus and at the botanical gardens of the Highlands Biological Station set aside for milkweed (the only plant monarch caterpillars eat) and other native plants to flourish.

“We have spots across campus that we tend by, well, not really tending that much at all, at least in terms of mowing or weed-eating,” said Vicky Heatherly, an agriculture and horticulture specialist with university Facilities Management. “We plant milkweed specifically to attract monarch butterflies and it benefits other species, too. Other insects feed on it and it’s the only thing that provides habitat for monarchs to lay eggs, develop into caterpillars to chrysalids and then emerge as a butterfly. Plus, having native plants supports birds and other species.

“It may look messy at times, but it is nature at its best,” Heatherly said. “It’s another thing that makes Western special and why I love working here.”

Roger Turk, grounds superintendent for Facilities Management, said the native plant habitats and flowering accent areas, no matter how small, serve multiple functions for the university’s landscape. “Our greenhouse staff propagates and plants thousands of annuals and perennials each year to be installed on campus. They also install many native and other flowering shrubs for landscape projects,” Turk said. “All those plants are huge attractors for pollinators, habitat for numerous species and having these ‘natural occurrence areas’ helps stabilize and reinforce the overall environmental setting. There is also a visual appeal, too. I always tell the grounds staff when it comes to how the campus looks, that we have one chance to make a good first impression, and that chance comes 365 days a year.”

For educators, the annual migration is an opportunity for instruction with living examples and natural variables. Recent attention has been shown to a reserved patch of milkweed alongside the A.K. Hinds University Center, where monarchs, caterpillars and cocoons have been observed.

“Students connect better when they can see and experience things for themselves, and how cool is it that 100 or so butterflies, a species that is being considered for the endangered species list, are going to emerge and head to the same spot in Mexico to join other monarchs from all across North America and overwinter? All because a small, 3-foot square patch of milkweed was planted,” said Aimee Rockhill, assistant professor of natural resource conservation and management.

Monarchs also are a good indicator of the overall environment, locally and globally. “When we study the natural world, we can often times infer how well an ecosystem is functioning based on the diversity of species we observe,” said Jane Dell, assistant professor of geosciences and natural resources. “Branching out even more to insects in general, they represent the most species rich group of animals across the globe with incredibly important roles in regulating ecosystem vigor. Especially here in the biodiverse region of Southern Appalachia, when we see declines in the diversity of insects, we know that there are issues happening that are affecting ecological function. Think about road trips you went on as a child - how often did you have to stop and wash off the windshield due to insects? Now reflect upon a more recent road trip. Most likely you didn't even have to use the windshield wiper once to clear off the insects. This is because we are in the midst of a global insect decline. The monarch is just another example of species experiencing human-caused declines.”

Observing monarchs also demonstrates how conservation and habitat management work. “I can use the material when we talk about support for wildlife conservation later in the semester. Some incentive programs for monarch conservation in North Carolina require a couple acres of land to be considered for funding and support,” Rockhill said. “Given that a majority of the lands in the state are privately owned, I think this is a good teachable moment to discuss incentive programs and assess what works and what does not. WCU’s little monarch population is a great example of how individual landowners can make an impact by planting patches of milkweed to support monarch conservation.”

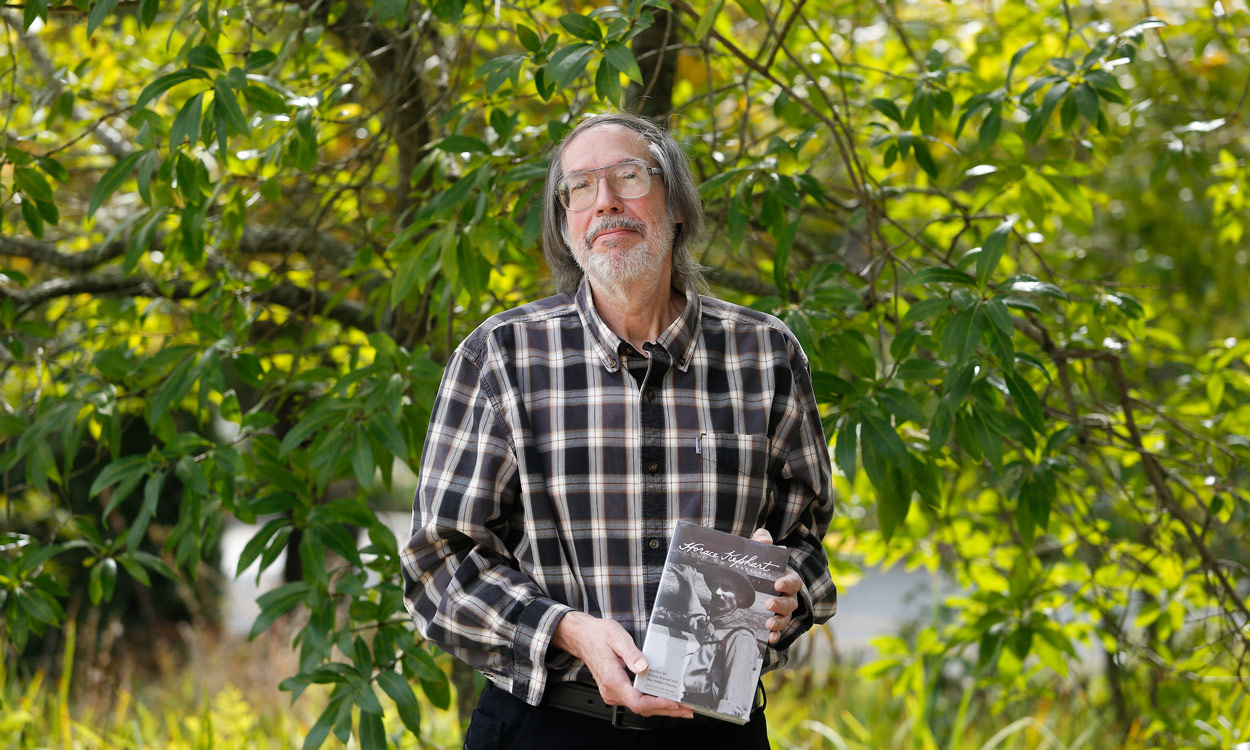

Pre-pandemic, students from Mountain View Intermediate School in Macon County would work with Jason Love, associate director of Highlands Biological Station, in a “Migration Celebration” each year to tag and release migrating monarchs as part of a project led by the University of Kansas. “There seems to be a growing recognition by the general public of the importance of native plants for native wildlife, including insects,” he said. “While pollinator gardens are great, I think we sometimes forget the roles that plants play in acting as host plants for many insects, the monarch and the milkweed being prime examples.”

Besides being beautiful, intriguing and photo-worthy, monarchs and the more than 5,000 related species of moths and butterflies also shaped the evolution of plants and continue to benefit mankind. “Many caterpillars are herbivorous, meaning they eat plants,” Dell said. “Because plants can’t get up and run away from predators, they have evolved mechanisms to defend themselves against herbivores. The compounds created in defense have been widely utilized by humans. From medicinal products to latex, or black pepper to the tannins that flavor red wine, we can thank our herbivore friends for helping to create these useful and tasty items.”