HUMBLE FIRST

It was 1987 when Michael Naylor ’82 MBA ’88 and several other Western Carolina University alums who were a part of the Ebony Club decided it would be cool to have an African-American reunion. And what would be cooler than to have WCU’s first African-American student attend the reunion?

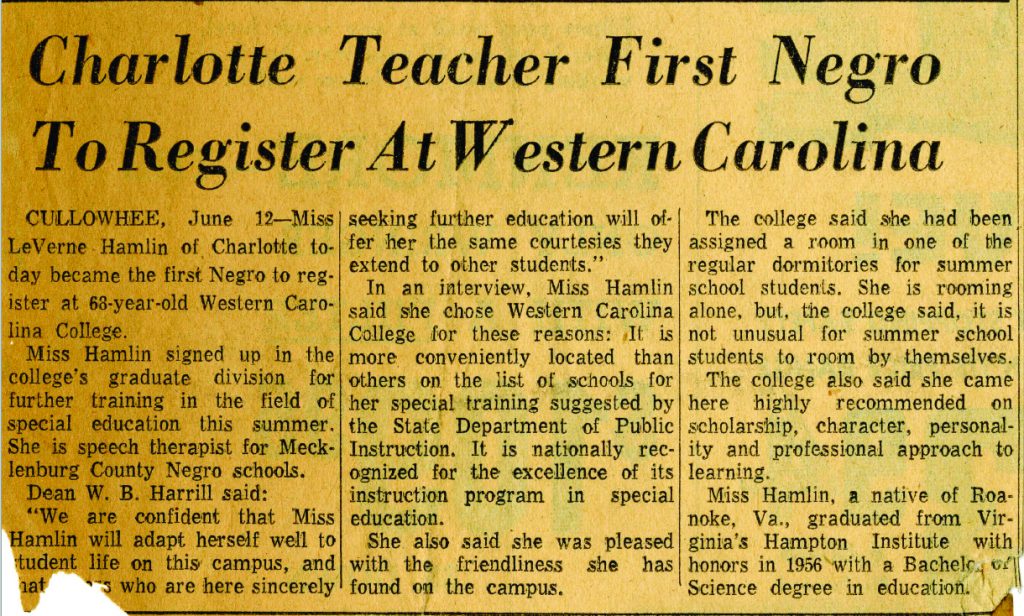

After some research, Naylor discovered that the first African-American student to be admitted to what was then called Western Carolina College was Levern Hamlin Allen. Naylor eventually tracked down Allen, who was teaching in the Washington, D.C., area at the time.

Levern Hamlin Allen studied diligently, hoping to get straight A’s. She was disappointed when she later learned that only pass/fail grades were given in her classes.

“I was just ecstatic when she answered the phone,” Naylor said. “I said, ‘I’m Michael Naylor from Western Carolina University. Do you know who we are?’ She was like, ‘Oh my goodness. Yes.’”

That was the start of WCU’s reconnection with the student who helped it become one of North Carolina’s first all-white institutions of higher education to integrate in 1957, just three years after the Supreme Court’s Brown v. Board of Education ruling that segregation in public schools was unconstitutional.

Sixty-one years later, WCU’s Board of Trustees decided to honor Allen by naming its new 600-bed residence hall, currently under construction, Levern Hamlin Allen Hall. The hall, slated to open this fall, is the first building on campus to be named after an African-American.

“It’s well-deserved and almost overdue,” said Naylor, who is president of the newly formed Western Carolina University African-American Alumni Society. “In terms of the contribution she made to the university by essentially integrating the university, it’s just a phenomenal accomplishment to be recognized. As an alum, I am very honored that the university worked through that and was able to name this very modern, state-of-the-art facility after her.”

For Allen, Naylor’s call to come to the reunion was nothing like the one she got from Wardell Townsend ’75, a member of WCU’s Board of Trustees, informing her that the board hoped to name a residence hall in her honor and that Interim Chancellor Alison Morrison-Shetlar and Chief of Staff Melissa Canady Wargo would like to meet with her to seek her approval. It was more like the call she received when former Chancellor John W. Bardo called to say she was selected to receive an honorary doctorate of humane letters in 2006.

Except this was history in the making.

“Now it’s like, a dorm? A building?” said Allen, who is 82 and living in a retirement community in Silver Spring, Maryland. “My children have gone bananas. They said, ‘We will be in history forever and ever.’ I said, ‘Until they tear the building down.’ It has generated some excitement within the family.

“I’m trying to respond with all of that excitement. But I guess it really hasn’t sunk in. When a building is named for someone, they usually have contributed large amounts of money to the project, or to the school, or something like that. But just for that to happen because I am who I am, it’s kind of strange for me. It’s hard for me to deal with that.”

Allen was an honor graduate of Hampton Institute (now Hampton University) in the spring of 1956 and accepted a job in Charlotte with the Mecklenburg County School System as a speech therapist. After arriving in North Carolina, she learned that the state’s teacher certification requirements were different than those in Virginia. She needed nine credits in special education to be certified.

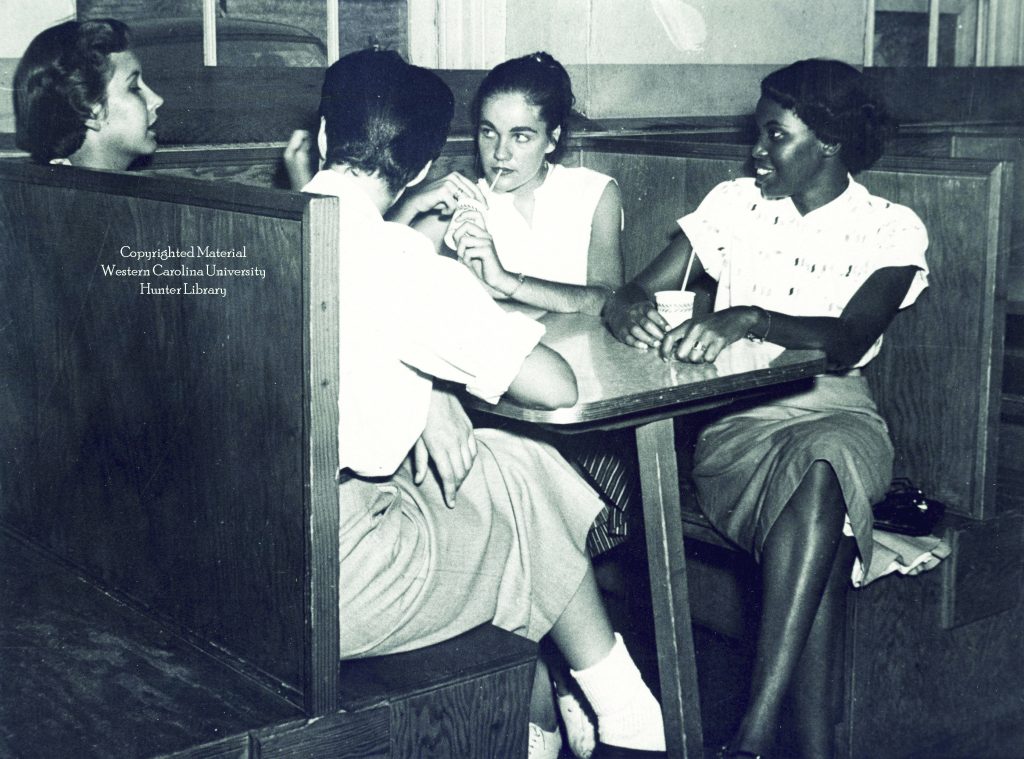

Levern Hamlin Allen goes through the line with other students at Brown Cafeteria.

Allen lived near Johnson C. Smith College in Charlotte, but it didn’t have a special education department. After writing the State Board of Education seeking schools she could attend, Allen learned that WCU was the only one to offer the three courses she needed. She applied and was accepted in the summer of 1957.

Her long trek to Cullowhee would begin from her parents’ home in Roanoke, Virginia. The only thing she knew about Cullowhee is that it was southwest of Asheville. With her Chevy loaded with her belongings, Allen made the trip alone, the farthest she had ever driven. “My dad said, ‘You made this mess. You have to go do it by yourself,’ ” she said. “I mapped out a route. You know how AAA used to give out TripTiks

a long time ago? It was that kind of thing. I mapped out my route.”

About an hour into her trip on that hot June day, Allen’s muffler went out around Martinsville, Virginia. “It sounded like a truck was behind me too close,” Allen said. She had it replaced, and continued her journey.

Just prior to reaching Cullowhee, Allen stopped at a gas station because she wanted to arrive on campus with a full tank of gas. She drove to the top of the hill where Joyner Building stood.

One of the things Levern Hamlin Allen enjoyed most about her time in Cullowhee was the friendly people she encountered.

“When I got there, I pulled in and I tried to fan myself because it was hot with no air-conditioned cars,” Allen said. “I had cramps in my feet. It must have been like 3 or 4 o’clock in the afternoon.”

As she prepared to register for her classes, Allen remembers feeling extremely nervous. Not because she was stepping into an environment where she would be the only African-American. She had experienced that before as a teen in Roanoke when she would go to the YWCA.

“This was different because the times were different,” Allen said. “It was about three years after Brown v. The Board of Education. People were not acting nice throughout the country, especially in the South. I was pretty nervous, but by the end of the week, it was OK. I came in on a Tuesday (the day after registration) under the direction of the college. By Friday, I was OK. Everybody was OK. There was no problem.”

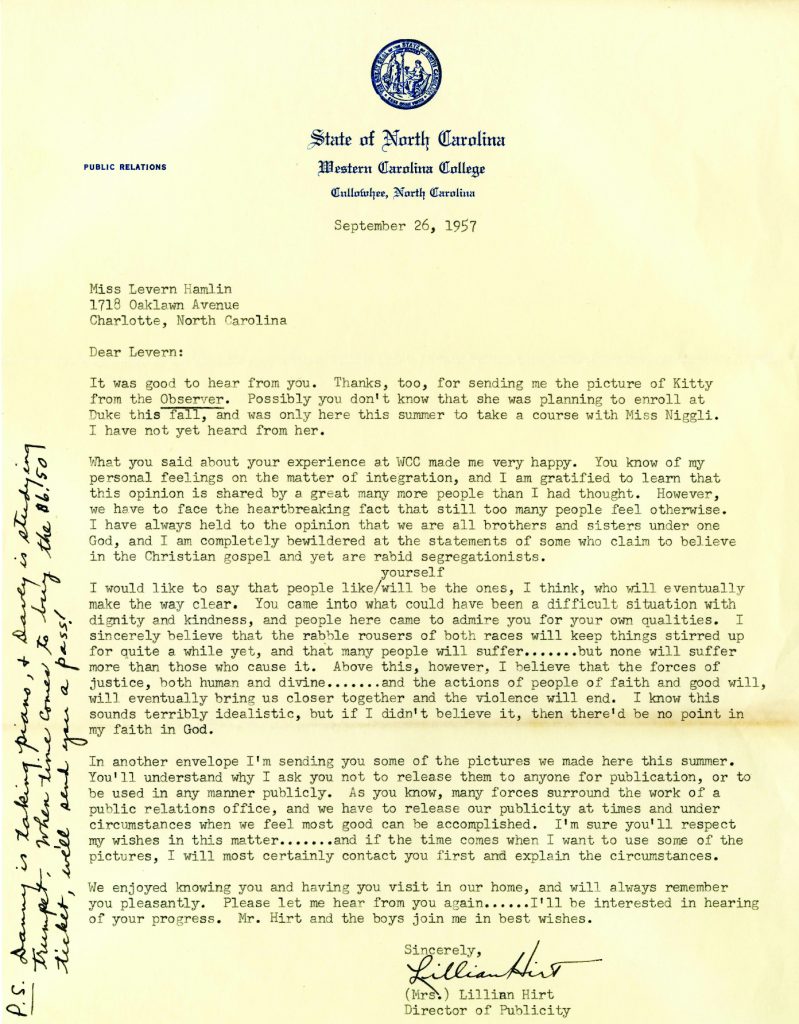

Allen would be under the careful watch of Lillian Hirt ’69, WCC’s director of publicity. Hirt interviewed Allen, wrote a news story and took photos of Allen, all of which she provided to media outlets. Allen credits Hirt for making sure things ran smoothly. “She was very, very instrumental in making sure that this was a success for Western. I would give her 100 percent of the credit. I don’t know if she deserves it or not, but from where I stand, she was the person who made everything come together and click.”

During that first week, students would come up to Allen to introduce themselves, putting her nerves and fears at ease. The professors were just as accommodating, she said. Little did she know, people in Sylva already knew who she was.

One day, Allen went to the local bank to cash a check. She brought several pieces of identification to ensure there would be no problems. As Allen walked up to the teller, she was greeted, “Hi Ms. Allen.” “I thought that was very interesting,” Allen said. “It showed the compassion that the town had for doing what was right at the time.”

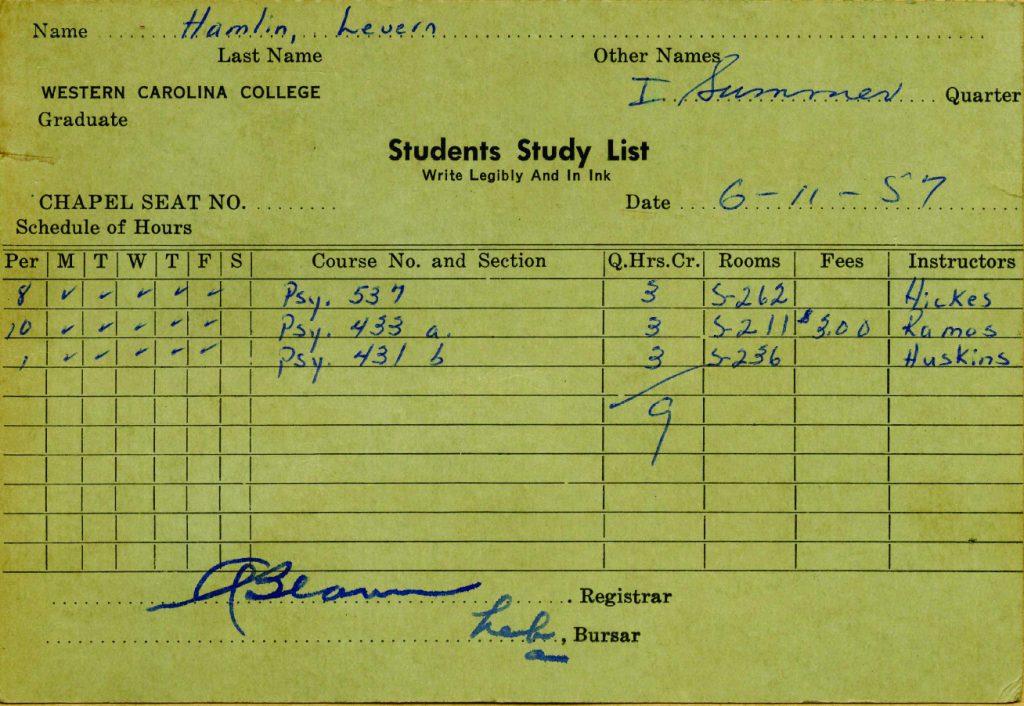

Allen’s three classes were “Psychology of Exceptional Children,” “Re-Education of the Acoustically Handicapped Child” and “Social Treatment of the Mentally Retarded.” She studied diligently with hopes of achieving all A’s, only to be disappointed to learn that pass/fail grades were given.

“I was looking for A, A, A. Isn’t that crazy?” Allen said. “You go a whole semester and you don’t know what the grading system is. You do your papers and you turn your stuff in. That was new and different to me.”

Allen did befriend an African-American family, the Lackeys, from Sylva. The family, which had a daughter her age, would invite Allen over for Sunday dinners. They also went to Cherokee to see the play “Unto these Hills.”

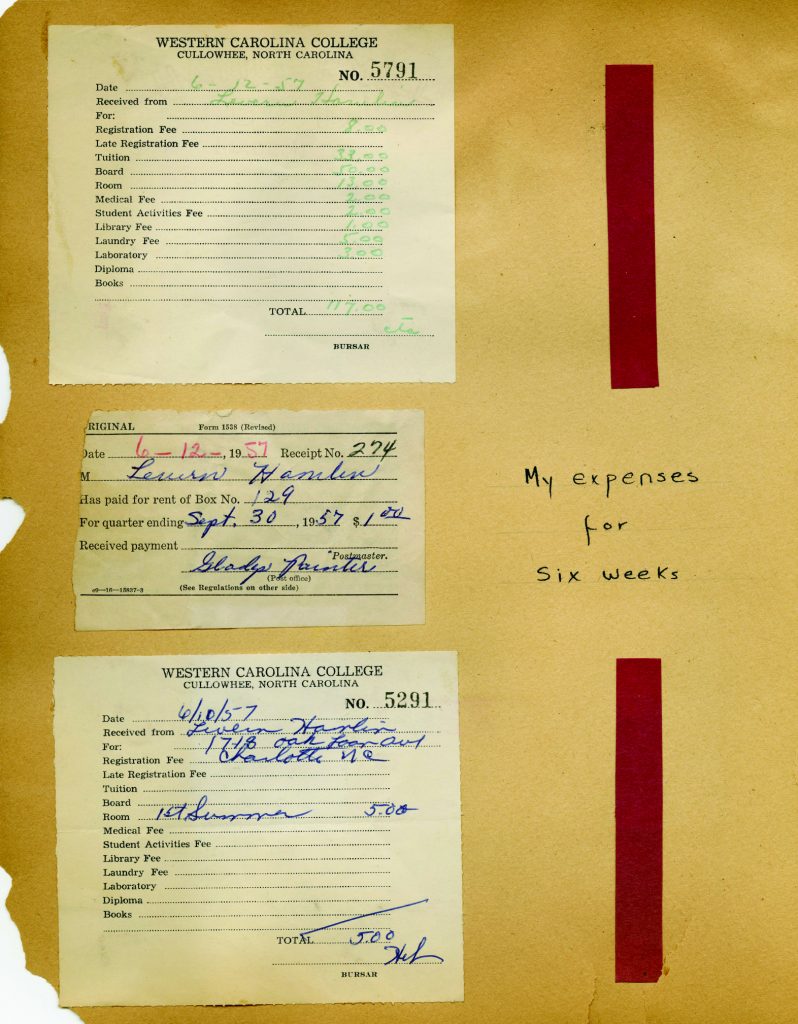

During her summer in Cullowhee, Allen kept a journal, complete with pictures, letters, notes and mementos of her experience. “I just knew that this was something special and different,” Allen said. “I wish I had kept it instead of giving it back to Western so soon because I would have names that I don’t remember now. I didn’t think of it as being historical, but I knew it was special, and it was special to me.”

In all, her time in Cullowhee was a far better experience than Allen expected. She came with thoughts of the violence that had taken place at other schools trying to integrate. She not only left with the credits needed for her teaching certificate, but she did so with pleasant memories of the people who crossed her path.

“I felt like the university put itself out there for me, so this was something that I needed to do for them,” Allen said. “It felt awkward to have all of the attention placed on me, but I knew what the time was. That was a pretty awful time. To show somebody else, hopefully the world, that this can work, you can do this without the violence and fighting, was meaningful to me. I didn’t mind doing it.”

On her return to Roanoke, Allen did something she had never done. She drove on the Blue Ridge Parkway.

Levern Hamlin Allen (center, inset photo) was reintroduced to WCU in 1987 when she was invited to attend a black alumni reunion where she shared her story.

As Allen married and went on with her teaching career, her association with WCU faded into the history books. That was until Naylor and the Ebony Club reached out to see if she would come to Cullowhee and share her story as the university’s first African-American student.

Naylor picked up Allen and her husband from the Asheville airport and brought them to Cullowhee. “It was a wonderful opportunity to talk with her about her experience coming to Western at that time, and in general about her life experiences since then,” Naylor said.

It was about a year later that WCU Chancellor Myron L. Coulter reached to out Allen to see if she would serve on its Board of Trustees. “I was like, ‘Are you kidding?’ ” said Allen, who served two terms on the board. In 2006, she received another call from WCU. This time she was informed that she was going to be awarded an honorary doctorate of humane letters.

“That was kind of scary,” Allen said. “It was something that was unexpected. I had

served on the search committee that brought John Bardo there. I had gone to Bridgewater,

Connecticut, to interview him, and to interview people about him. I came back and

told the board this is the man, and sure enough, he was. When he stood there and read

that citation, it was just a feeling that all of these things were before me and I

was there listening. It wasn’t an obituary; I was participating. It was kind of hard

to keep it together.”

“That was kind of scary,” Allen said. “It was something that was unexpected. I had

served on the search committee that brought John Bardo there. I had gone to Bridgewater,

Connecticut, to interview him, and to interview people about him. I came back and

told the board this is the man, and sure enough, he was. When he stood there and read

that citation, it was just a feeling that all of these things were before me and I

was there listening. It wasn’t an obituary; I was participating. It was kind of hard

to keep it together.”

On the morning of Thursday, Nov. 29, 2018, WCU announced that it would name its new residence hall after its first African-American student, Levern Hamlin Allen. Thanks to Twitter, Instagram and Snapchat, the news blew up across campus.

Levern Hamlin Allen examines the scrapbook she made of her summer of 1957 in Cullowhee.

“Everybody was screenshotting it and saying, ‘Look everybody. It’s happening. Look at this.’ It was everywhere,” said Erica Davis, a senior accounting and finance major from Charlotte. “We were all really excited about it. Everybody went and read the article on it to make sure this was happening and not just something that might happen. We made sure we got the word out.”

Terrell Chandler, a junior psychology major from Raleigh, also learned of the news through social media. “Some people I know posted it. Just seeing an African-American woman getting a building named after her is really big, capitalizing on the ultimate minority for the most part, it’s a big deal,” Chandler said.

For Davis and Chandler, both African-Americans, a sense of pride came over them, along with a sense that this was something that was long overdue. Allen Hall will be the first building on the WCU campus to be named after an African-American.

“I was very excited,” Davis said. “Of course, I thought, ‘It’s 2018. Why did it take

so long?’ To me, it’s somewhat of a showing that Western is trying to make a stride

toward actual diversity in a time where diversity is just a word instead of an action,

especially at predominantly white institutions. I think it’s a push for them right

now showing that they are trying to supposedly show us some diversity instead of just

talking about it. There are so many issues going on within society. I think now is

the time for a lot of large institutions and organizations to make pushes like this.”

“I was very excited,” Davis said. “Of course, I thought, ‘It’s 2018. Why did it take

so long?’ To me, it’s somewhat of a showing that Western is trying to make a stride

toward actual diversity in a time where diversity is just a word instead of an action,

especially at predominantly white institutions. I think it’s a push for them right

now showing that they are trying to supposedly show us some diversity instead of just

talking about it. There are so many issues going on within society. I think now is

the time for a lot of large institutions and organizations to make pushes like this.”

Chandler is president of WCU’s chapter of the NAACP. He, too, is glad to see WCU improving its diversity. “I was really thinking I wouldn’t see something of this magnitude happening,” he said. “We can now really find hope. We can see that we are advancing as a culture out in this predominantly white area. Things are on the up and up. I truly do believe the African-American community here is going to become more inclusive, or more heard. I think that’s a very important and key concept for us. This is a big moment in history for us.”

For Dana Patterson, director of WCU’s Intercultural Affairs, the announcement made

her proud to be a staff member on campus. She also appreciated that the university

decided to do this while Allen is still alive.

For Dana Patterson, director of WCU’s Intercultural Affairs, the announcement made

her proud to be a staff member on campus. She also appreciated that the university

decided to do this while Allen is still alive.

“It was a very proud moment in our history,” Patterson said. “It’s a way of honoring her and the decision she made to come and be the first person here as a black woman,” Patterson said. “She lived at the intersection of so many different identities – being black, being a woman, being the first and also being Appalachian. All of those things combined really made her have that much more to overcome. What better way to honor and lift her up? Future generations will have a chance to hear about her, know what she did and know her story.”

Patterson said she hopes this historic occasion will inspire other students to document their own experiences as students at WCU as a way of acknowledging that the struggle is real.

Several predominantly white institutions across the country recently have struggled with what to do with names of buildings and statues that commemorate Confederate Civil War heroes.

That makes the naming of Allen Hall and last year’s renaming of Central Hall to Judaculla

Hall to honor the Eastern Band of Cherokee Indians that much more significant, said

Elizabeth McRae MA ’96, who holds WCU’s Creighton Sossomon Professorship in History.

That makes the naming of Allen Hall and last year’s renaming of Central Hall to Judaculla

Hall to honor the Eastern Band of Cherokee Indians that much more significant, said

Elizabeth McRae MA ’96, who holds WCU’s Creighton Sossomon Professorship in History.

“I think that representation is really important in the things we choose to celebrate as a university, a state and a nation,” McRae said. “I hope that would be part of a larger process that also addresses the real kind of divisions we have among students on this campus and that the efforts are not just to celebrate the past, but also to shape the present and the future in meaningful ways. I think that’s one step, but it’s not the only step that needs to be taken right now.

“I am proud that we have Judaculla Hall and now we have the hall named after (Allen). I think it’s part of a really necessary development that our universities reflect the communities that they serve, the struggles to make them inclusive and make higher education equitable. I’m glad Western is participating in the process of reflecting a history that actually reflects both the populations that we serve and the historic struggles that we’ve had to make as a public university to really serve the public,” she said.

Current and future African-American students at WCU can now stroll up the hill on

Central Drive, look at Allen Hall and see a building that represents their place in

history at the university. It’s a visual realization that they, too, can make their

mark and leave a lasting impression in Cullowhee.

Current and future African-American students at WCU can now stroll up the hill on

Central Drive, look at Allen Hall and see a building that represents their place in

history at the university. It’s a visual realization that they, too, can make their

mark and leave a lasting impression in Cullowhee.

“This is big,” Chandler said. “I really believe there is a crisis in African-American self-identity. We don’t have enough monuments or enough history. There is a lot of history that a lot of us don’t know about. Creating history is becoming a newer concept. This building being named after an African-American woman is creating history, not only for Western, but for African-Americans in general. I believe that is a huge step forward.”

While Allen still hasn’t totally grasped the idea of having a residence hall in her name, her daughter, Alyss Grear, who lives in Columbia, Maryland, has clearly been the most excited family member. About two weeks after the announcement, Grear held a party in her mom’s honor for family and friends.

“I was extremely excited and proud,” Grear said. “She called me right after they told her. It’s such an honor. It’s like a lifetime achievement award. I mean, how many people can say they have a building named after them. I’m just so proud of her.”

Growing up, Grear and her brother, Joseph Allen, knew their mom was the first African-American to attend WCC, but Allen rarely spoke of it, and when she did she downplayed the significance of it. “She just said she went to her classes and did what she had to do,” Grear said.

It wasn’t until Grear was an adult that she began inquiring about her mother’s time

in Cullowhee. “We asked questions like, ‘What was it like’ and ‘How did they treat

you?” Grear said. “We knew how they treated blacks back then from what we read and

they were not nice. I was pleasantly surprised when she said everyone treated her

so nice.”

It wasn’t until Grear was an adult that she began inquiring about her mother’s time

in Cullowhee. “We asked questions like, ‘What was it like’ and ‘How did they treat

you?” Grear said. “We knew how they treated blacks back then from what we read and

they were not nice. I was pleasantly surprised when she said everyone treated her

so nice.”

Several of Allen’s friends and family members are planning to make the trip to Cullowhee this fall for the dedication ceremony, some of whom had no idea of Allen’s story. They’ll get to stand on the hill in front of Roberston Hall where Allen resided and look down on the campus while she reminisces on the summer of ’57.

As it slowly sinks in, Allen can’t help but think about what her parents would say. “My dad would be extremely proud,” she said. “My mom would be cool. He was still living when I was asked to join the Board of Trustees and he said, ‘I remember when you went down there,’ and he pulled out some old newspaper clippings from way back. He would be beside himself. He would be telling the boys over at the pool hall about his baby girl.”

A rendering of Allen Hall.

Allen said she doesn’t want people to thank her for helping to integrate WCU. She believes anyone who was in her situation would have done the same thing. In her eyes, it was circumstance that led to her place in the university’s history.

“It wasn’t something that was planned,” Allen said. “No organization was behind me. I needed nine hours so I went. So, if you want to say thank you for doing that and going forward, that’s fine. But I don’t feel special for doing that. If I opened the doors so that somebody else could come, that’s good, too. It was just something I needed and so I went. And now, see where I am. Wow. From a need for nine hours to having a building named after me.”