Making History:

John C. Campbell Folk School

The John C. Campbell Folk School was established in 1925 in Brasstown, a rural community in the westernmost corner of North Carolina. With the help of Marguerite Butler, Olive Dame Campbell established the folk school in honor of her late husband, John, who earlier chronicled life in the region. In its embrace of the Danish folk school model and its emphasis on agriculture, the John C. Campbell Folk School mission and goals differed from other Craft Revival institutions. In 1928 the folk school sponsored “Handwork Week” to highlight traditional craft skills. In the 1930s, the school began teaching woodcarving and established a community group that became known as the Brasstown Carvers. Upwards of 75 local residents participated in the program. Today’s Brasstown Carvers continue to make highly detailed carvings of farm animals and nativity figures.

There was no plan or path in the design of early Craft Revival institutions. Most grew organically with only vague notions of goals and objectives. Not so with the John C. Campbell Folk School. Its establishment was preceded by study, theory, and a planned implementation. John and Olive Campbell were introduced to the concept of the Danish folk school by P. P. Claxton, an educator from Tennessee, who became the U.S. Commissioner of Education. In 1914 the Campbells planned to visit Denmark, but cancelled their trip when war broke out in Europe. John Campbell died in 1919 without ever making the trip to see Danish folk schools in operation. Three years later, in 1922 and with a grant from the American Scandinavian Foundation, Olive set sail for Denmark. She spent 18 months studying folk schools and folk culture in Scandinavia and in England. Her sister, Daisy Dame, and colleague, Marguerite Butler, a teacher at the Pine Mountain Settlement School in Kentucky, accompanied her. 1.

The John C. Campbell Folk School was modeled after a particular type of school, the folkehojskoler in Danish. When Denmark became a democratic society, the nation’s politicians wisely concluded that the country would benefit from educating its voting public. While private schools were available to the wealthy, these new publicly funded schools were aimed specifically at the “folk”—regular working people. Olive Dame Campbell’s yearlong folk school study culminated in a book, The Danish Folk School. She credited the movement to Nikolai Grundtvig (1783-1872), who espoused the value of the “Living Word,” a personal connection between students and their teachers. Campbell applied this idea to her plan, describing the “distinguishing feature of the true folk school” as “living together as family.” She proposed the “educational value in the doing of life’s work” over the “book standard of education.” Even though the U.S. Dept of Education studied Danish folk schools in the early 20th century, only a few American schools were established upon this European model. The short-lived Stanley-McCormick School in Burnsville, North Carolina was patterned after Fircroft, an English folk school; Berea College sponsored a folk school “experiment” in the 1920s; and the Highlander Folk School in Tennessee (still in operation today) taught social change over tradition. 2. It was the John C. Campbell Folk School in Brasstown that came to epitomize the American folk school.

After the three women returned to America, they began to look for a place to site a school. In Southern Mountain Life and Work, Campbell described her desire for an ideal location and stressed the importance of community ownership. “[We are] looking for a natural center,” she wrote, “where creeks come together…a section with agricultural possibilities.” A few months later, in September 1925, Marguerite Butler arrived by train in Murphy, North Carolina. She and Campbell had been actively looking at sites for seven months and had nearly settled on a location in West Virginia. It is not clear whether Brasstown citizens had any role in Butler’s initial visit to Murphy. She wrote that the area was suggested to her by a welfare worker. No matter the circumstances that brought Butler to Murphy, once there, local citizens actively courted her. 3.

Marguerite Butler was in town just a few days when she was visited by Fred O. Scroggs, the owner and operator of a general store in nearby Brasstown. Arriving with his father, L. L. Scroggs, the two men made a case to locate the school in the Brasstown community. When Butler toured Brasstown a few days later and attended a meeting at the Methodist Church South, she was surprised to find over 200 people had come to hear the options. Butler recalled one meeting:

At about seven o’clock that night the Baptist Church on Little Brasstown was crowded to the doors; wagons and machines stood everywhere on the hillside... For over two hours and a half I talked and answered questions. 4.

On October 1st local citizens drafted a summary of their meetings. Posing eleven questions, the group responded unanimously to each one. Curiously, one question indicates that the community was thinking broadly, “How many states are within reach?” they asked. More to the point, they asked themselves, “What do they have to offer?” and answered, “Land, labor, material, and folks.” The decisiveness of their response was impressive. After Butler left Murphy, she received a letter that claimed,

The interest of our people in ‘the school’ has not only not abated, but appears to be increasing. Not a day passes that some of them do not call to ask about it... I have never seen people so hungry for knowledge. 5.

The persistence of Brasstown citizens was convincing. By the time Olive Campbell arrived to see Brasstown and meet with local representatives in November, the community had amassed 116 pledge cards, donating everything from flower bulbs to farmland. In its persistence, Brasstown beat out West Virginia as the home of the new folk school. Incorporation papers were drawn up immediately and the folk school became a reality. The school was located on 20 acres of land donated by the Scroggs family. 6. In December 1925 Olive Dame Campbell and Marguerite Butler moved into the small farmhouse that served as the school’s center for its first few years.

The Brasstown community pledged land and work necessary to construct a school

The spring of 1926 must have been an exceptionally busy time for Olive Campbell. While trying to get a new school off the ground, she continued to preside over the Conference of Southern Mountain Workers in Knoxville. That was the year that Allen Eaton came and spoke on handcraft taking a central role in mountain work. Initially, the John C. Campbell Folk School focused on agriculture rather than crafts. The school motto—“I sing behind the plow”—and school logo—of a farmer working with a team of horses—are evidence of the school’s self image as an agricultural haven. Campbell wrote about the need for a mountain school, using an eloquent metaphor based on the land. Of mountain youth, she wrote,

The stronger did not stay to fertilize the soil of mountain life, but went, like top-soil in the streams, to enrich the land beyond the mountains, leaving behind eroded fields and diminishing hope. 7.

Maintaining an emphasis on cooperative farming, the folk school facilitated the establishment of the Brasstown Savings and Loan, a credit union; a Farmers Association and poultry hatchery; and the Mountain Valley Creamery cooperative.

In May 1926 Campbell and Butler were joined by Georg Bidstrup, a Dane who came to the school to run the farm and provide recreational activities for students. A month after Bidstrup’s arrival, Leon Deschamps arrived. A forester and engineer, Deschamps remained for 17 years, shaping the school’s facility. During his tenure, he constructed a springhouse, dairy barn, and co-op creamery. A mill house pumped water to a reservoir uphill, so that water was gravity fed to the school. In addition to school construction, Deschamps taught surveying, drafting, and mechanical drawing. In March 1926 the John C. Campbell Folk School circulated its first newsletter outlining the school’s philosophy. The school set “no requirements, gives not examinations, offers no credits,” it read. This conceptual framework was supported by the rhetorical question, “How shall we keep an enlightened, progressive, and contented population on the land?” In February 1927, the John C. Campbell Folk School hosted a weeklong experimental school session, what Olive Campbell’s sister Daisy called the “first go-to-school week.” Campbell spoke on history, Butler spoke on travel, Deschamps covered topics in forestry. Later, Fred O. Scroggs talked about archeology. 8.

In December 1927, the folk school began taking students in a regular session that lasted from December until early spring, when farm families had to return to their primary livelihood. In spite of an early plan to establish a boarding school of 100 boys and girls, enrollment in the 1920s numbered in the single digits. In 1930 the school had completed its main building, Keith House, which housed classes, administration, and the girls dormitory. Boys lived at the other end of campus in the Mill House, also home to the farm operation. By 1932 there were 22 students whose average age was 22 years old. Besides their schoolwork, students maintained the school and farm. Boys worked on the farm; girls in the laundry. Both boys and girls cooked and served family-style dinners. All activities, including chores, were considered valuable to a young person’s education.

We emphasize the experimental character of the John C. Campbell Folk School. It must find a new approach to old subjects; it must develop a new technique of teaching. Furthermore, if the teaching is to enrich rural life, it must be rooted in a deep belief in the country; not perhaps as it is, but as it may be: its power to satisfy; to offer a full life. 9.

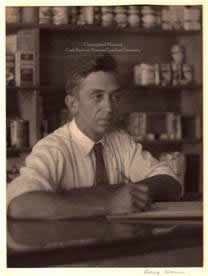

The 1930s was a time of excitement and activity. The school newsletter notes the “special treat, a three weeks visit from Mrs. Doris Ulmann and John Jacob Niles.” Ulmann, a photographer, returned many times over the next year to take photographs in the region; Niles, a composer and musician, shared a love of music with Olive Campbell. In spite of the worsening Depression, the 1930s remained a high point in the folk school’s activity with many overnight guests. A visit by Arthur Morgan, director of the Tennessee Valley Authority, caused particular excitement throughout the community.

We are accustomed to guests arriving by foot, horse-back wagon, car or truck, but never as two appeared this summer—by airplane... The plane was trying to land... in a neighbor’s field... The send-off was even more impressive. Old and young mysteriously appeared, for this was Brasstown’s first airplane. 10.

One aim of the John C. Campbell Folk School was to connect with the local community, not just to the students who attended the school, but their families and neighbors as well. Within its first year of operation the school formed a Women’s Community Club. Its 21 members met monthly for dinner and memories, “recalling the life of bygone years.” Like other Craft Revival centers, the folk school placed a value on enduring traditions. A Log Museum was built on campus to house traditional artifacts. In 1926 Marguerite Butler, writing to her mother, described the “pounding and sawing away on the museum...daub[ing] the chinks with mud, [and] laying the puncheon floor.” Once readied, the museum awaited “wagonloads” of “relics” for installation. Every July 4th the school celebrated Independence Day by hosting an “Old Folks Dinner” on the grounds. A 1927 newsletter included quotes highlighting recollections of tradition. “I cooked over the open fire for eighteen years,” recalled one old timer. 11.

It was not until 1929, however, that mention is made of “Handwork Week” and the formation of a local Handicraft Guild. Perhaps the timing of the folk school’s craft programs was a reflection of the growing interest in handcraft within the broader western Carolina community of mountain workers. There was plenty of incentive for the folk school to consider adding handwork to its program. In 1929 a core group of Craft Revivalists—including Olive Campbell—met to discuss the formation of a cooperative marketing guild; the Weaving Institutes at Penland were attracting outside students. The Conference of Southern Mountain Workers was regularly bringing in guests who spoke on handicrafts. Craftwork took firm root at the folk school during the summer of 1930, the first summer of the school’s “short course,” a ten-day program held each June. Clementine Douglas, owner of the Spinning Wheel, a museum-style storefront in Asheville, spoke on the history of weaving. Parker Fisher, a Hartford Theological graduate and old friend of John Campbell, directed the boys in making tool-chests. Margaret Campbell, from Tennessee’s Pleasant Hill Academy, a school with a successful carving program, taught carving to both boys and girls. Louise Pitman and Jane Chase taught weaving. Besides those that came to teach, other craft organizers attended the program, including Helen Dingman from Berea and Evelyn Bishop, Director of the Pi Beta Phi School in Gatlinburg (today’s Arrowmont School of Arts and Crafts). 12.

The folk school, like other Craft Revival schools, sponsored a dual program of handicrafts: the on-campus instruction of its students and the off-campus production of community crafts. Olive Campbell explained the process, “Our craftwork…is done partly at the school and partly in the homes,” she wrote. While school records made clear that the handicraft guild and school were separate (perhaps for financial reasons), in their day-to-day operation, boundaries were blurred. Guild products included baskets, brooms, and chairs, all made in the homes of local citizens. In 1932 crafts were introduced as part of the school program, a “decided gain,” according to school Director Campbell. Eight looms were installed in a weaving room in Keith House, the school’s community center. Girls were taught to weave and boys were taught to carve. Throughout the 1930s the folk school continued to maintain its regular four-month residential program and its summer short course. Demonstrating a renewed confidence, the school newsletter claimed, “The John C. Campbell Folk School is no longer an experiment.” 13.

Throughout the 1930s, several craft programs were established. Parker Fisher taught woodworking and carving during the first half of the decade. In 1935 Murrial Galt arrived to teach weaving and carving. Galt was an occupational therapist at Walter Reed Hospital; by 1937 she had married “Dub” Martin, a local man. She lived her long life in Brasstown, celebrating her 100th birthday at the school in 2002. Louise Pitman had fast become an expert on vegetable dyeing. She ran the handicrafts program, handling the business aspect of the guild, and in 1932, held the title of Director of Handicrafts. In the late 1930s and early 1940s, Oscar Cantrell and Herman Estes, both local men, joined the staff. Cantrell taught blacksmithing and Estes taught furniture making. But with new additions, the 1940s brought departures as well. Leon and May Descamps left the school in 1943 and Louise Pitman followed in 1945. Olive Dame Campbell retired in 1947 after 22 years as Director.

Throughout its early history, the John C. Campbell Folk School received donations and appropriations from three church boards—Presbyterian, Congregational, and Episcopal. At one time it received support from the Carnegie Corporation as well. Still, by 1940, there was concern over the school’s “falling income,” perhaps a residual effect of the Great Depression. In spite of financial woes at the school, the community carving program was thriving. In 1935 almost $2,000. was paid to 52 community craft workers; by 1941, 67 carvers made $7,000. Carving took on importance in the community with upwards of 75 carvers participating, including multiple generations within large extended families. In the 1950s, the carving group formally became known as the Brasstown Carvers and continued to produce small, hand-held animals and nativity figures for another half century. 14.

In 1946 the John C. Campbell Folk School received approval from the State Department of Education to serve as a site for veterans who wanted to take advantage of the GI Bill. By the following year, the school boasted of a “full enrollment” with the GI Bill paying for veterans’ tuition. World War II veterans took blacksmithing and woodworking; Korean vets did cabinet work and ironwork. At many Craft Revival schools, enrollment shifted from mountain workers, occupational therapists, and craftsmen to veterans and public school teachers. In 1947 the folk school held a special workshop for 50 county school superintendents and school principals and added a two-week camp for children. These changes marked the end of the period known as the Craft Revival as the country entered a post-war era of American culture. Like other Craft Revival institutions, the John C. Campbell Folk School continued to promote the preservation of tradition. Its 1929 school newsletter is evidence of tradition’s enduring persistence. “Our Danish copper bell…rang its summons for nine o’clock morning song,” it reads. Today, almost 80 years later, 21st century visitors to the folk school begin their days in just the same way. 15.

- M. Anna Fariello, 2007

See More: About the John C. Campbell Folk School

1.

Olive Dame Campbell, The Life and Work of John Charles Campbell (Madison, Wisconsin: Privately printed, 1968) 205. Olive Dame Campbell to P. P. Claxton Feb 26, 1931.

2. Olive Dame Campbell, The Danish Folk School: Its Influence in the Life of Denmark and the North (New York: Macmillan, 1928) 61. Olive Dame Campbell, “Progress of the Folk School Movement,” Southern Mountain Life and Work I, No. 2 (July 1925) 18. Campbell reiterated these two main points—the school as “family” and a “school which seeks to fit for life”—in the school’s April 1928 newsletter. Mrs. John C. Campbell, “Roundtable on Adult Education,” Southern Mountain Life and Work II, No. 2 (July 1926) 15. Helen Dingman, “Folk School in Berea,” Southern Mountain Life and Work I, No. 2 (July 1925) 16.

3. Campbell, “Progress,” 18. Marguerite Butler, “Early Days of the John C. Campbell Folk School,” 1. This undated typed document, signed by Marguerite Butler, gives the name of Ann Ruth Metcalf as the welfare worker who introduced Butler to the Murphy area.

4. Butler, “Early Days.” By “machines,” Butler meant cars!

5. Report of committee meeting to organize a folk school, dated October 1, 1925 and signed by Fred O. Scroggs and Carrie Clayton. John H. Dillard to Miss Marguerite Butler, October16, 1925.

6.

The initial 20 acres of land donated by “L.L. Scroggs and family” was Strange family land, passed down to Lillian Strange Scroggs, who was L. L. Scroggs wife and the mother of Fred O. Scroggs. The original acreage was augmented by the purchase of additional parcels.

7. [Attributed to] Olive Dame Campbell, “I Sing Behind the Plough,” (April 1938) 5.

8. Campbell, “I Sing,” 7. “Excerpts from the Memoirs of Leon F. Deschamps,” undated, unsigned typed document. A native Belgian, Leon Deschamps was married to May Ritchie, of Viper, Kentucky. The Ritchie family is interwoven throughout the Craft Revival story. Sisters May and Orlenia Ritchie were cornhusk doll makers; Edna and Jean Ritchie were musicians. For a very readable first-person account of the Ritchie family, see Jean Ritchie, Singing Family of the Cumberlands (New York: Oxford University Press, 1955). John C. Campbell Folk School newsletters: no. 1 (March 1926); no. 5 (April 1928); no. 3 (April 1927); no. 7 (May 1929). Daisy G. Dame, undated scrapbook, page 49, in the John C. Campbell Folk School Archive.

9. John C. Campbell Folk School 1 [school newsletter] (March 1926). Campbell, “I Sing,” 8. John C. Campbell Folk School 13 [school newsletter] (April 1932); no. 10 (Oct 1930).

10. John C. Campbell Folk School 16 [school newsletter] (Dec 1933).

11. John C. Campbell Folk School 4 [school newsletter] (Oct 1927). Marguerite Butler quotes are from two letters to her mother, written May 24, 1926 and another written on “Sunday afternoon,” circa 1926.

12. John C. Campbell Folk School 6 [school newsletter] (Nov. 1928). Allen Eaton spoke at the conference in 1926; Edward Worst in 1927. Olive Campbell attended both the 1928 and 1929 meetings, called to discuss the formation of a cooperative marketing guild. “Wood Carvings Occupy Places in White House,” Asheville Citizen, April 8, 1934. John C. Campbell Folk School 10 [school newsletter] (Oct. 1930).

13. Olive Dame Campbell to Camilla Short, Dec. 6, 1933. John C. Campbell Folk School 9 [school newsletter] (April 1930); no. 9 (April 1930). “Meeting of the [John C. Campbell Folk School] Corporation” May 7, 1932. John C. Campbell Folk School 16 [school newsletter] (Dec 1933).

14. John C. Campbell Folk School 25 [school newsletter] (Oct. 1940); no. 17 (April 1935); no. 25 (May 1941); John C. Campbell Folk School, The Brasstown Carvers with text by Bill Biggers, photographs by Werner Kahn and Bill Biggers (1990).

15. John C. Campbell Folk School 29 [school newsletter] (Oct 1947); no. 7 (My 1929). “Folk School is Approved for Vets,” undated, unknown newspaper clipping mounted in John C. Campbell Folk School Archive scrapbook #2.