The People:

Herman Estes

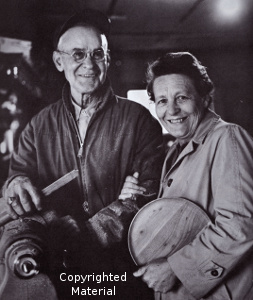

Herman Baker Estes (1897-1995) learned woodworking at Berea College. After several jobs and a five-year stint in the army, he moved to Brasstown, North Carolina, in 1939 to teach at the John C. Campbell Folk School. Unlike many community craftsmen who produced figurative woodcarvings for the school, Estes’ specialty was lathe work. He taught at the folk school for 15 years, retiring from teaching to produce and sell woodturnings full-time. He and his wife, Mabel, made bowls and platters in different shapes and sizes. They were successful makers, producing work for 16 shops in Chicago, Boston, and Florida. The couple regularly demonstrated at the Craft Fair of the Southern Highlands and were featured in Edward DuPuy’s book Artisans of the Appalachians.

Born in Lee County, Kentucky, Herman Estes parents were Moses and Melissa Newman Estes. Estes claimed to be a sixth generation descendent of the famous pioneer Daniel Boone, a blacksmith. Estes’ grandfather was a gunsmith who made muzzle-loading rifles “from the raw material right straight on up to the finished product.” His grandfather may have been the inspiration for Estes later interest in crafts. As a “wee small youngster,” he was intrigued by his grandfather’s workshop and, in particular, its foot-powered lathe. Fascinated with the process, young Herman stood on a box to reach the lathe. 1

Estes first learned woodworking at Berea College. Located in eastern Kentucky, Berea placed importance on local traditions, with particular emphasis on the skills of hand craftsmanship. By the time Estes arrived in 1911, Berea was well known for its craftwork; its woodworking program began at the start of the 20th century. A 1907 brochure includes a photograph of a Mission-style table captioned “Furniture of Ancestor’s Oak,” stressing tradition. The brochure claimed that, “Some of our mountain lads have been taught to make out of this stubborn wood, furniture which is most satisfying to sight and use.” 2 True to the prevailing Arts and Crafts philosophy of the time, Berea embraced both tradition and the use of native resources as suitable material for handwork.

Estes attended Berea College for three years; it is not known whether he graduated. For the next five years he served in the army, so it may well be that World War I interrupted his education. While little is known of Estes’ work at college, he was an eloquent writer who was interested in expressing his feelings about his work.

Craft may be defined simply as strength, skill, art….One must have the art or natural tendency to do the particular thing in craft and this can come by one way of saying genius, and another through years of patient practice, for no true craftsmanship is acquired easily. 3

After serving in the army, Estes became an apprentice with the Sellers cabinet making company in Troy, New York. He was there for four years, from approximately 1919 to 1922 or 1923. For the next five years, Estes worked heavy construction in Elizabethton, Tennessee, where he lived with his second wife, the former Mabel Amanda Riddle, and their two children. On the eve of the Great Depression, they moved to the family farm in Lee County, Kentucky, living with Herman’s father and eventually building a house of their own. The Depression played out differently in the southern mountains than in other parts of the US. The familiar city breadlines were absent in rural mountain communities where people grew much of their own food. In a 1965 interview, Estes provided details of his life at the time:

There was one year during the depression that our total grocery bill for a family of four was $12.05; that was the actual money we spent in one year, twelve months. Everything else we grew right on the farm; we ate like kings; we were pretty shabbily dressed sometimes, we had to wear sack dresses, the girls did. 4

During the Depression, Estes began making chairs to support his family. He constructed his chairs using traditional methods, putting them together “the old fashioned way without any glue.” He built a foot-powered lathe to turn the chair posts. Mabel Estes wove hickory bark to form the chair seats. “We’d sell them for a dollar apiece,” he recalled. Estes was proud of their craftsmanship. Seeing a few of their chairs 30 years later he said, “We saw some of those same chairs and they are just as solid as the day I built them.” 5

During the 1930s, Estes began his career as a teacher. Estes first taught at a Presbyterian settlement school in Kentucky, most likely the Hindman Settlement School in Harlan. He also worked at the National Youth Association, a Works Progress Administration program for youth. Ed Davis, a friend and gift shop owner from Berea, told Estes about the John C. Campbell Folk School. “He asked me if I was tied to my job. I said I wasn’t tied to anything but Mabel.” So Estes went to the school, first for an interview and, in July 1939, Herman and Mabel packed up their three children and headed for Brasstown, North Carolina. Estes taught at the John C. Campbell Folk School for more than a decade, retiring to devote time to his own woodworking business in the 1950s. 6

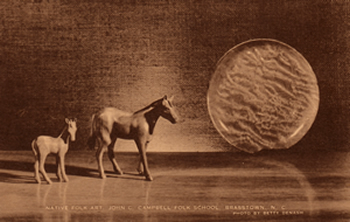

At the folk school, Estes worked in woodcraft with Murrial Martin and Louise Pitman. Martin taught carving and Pitman managed the carving business and taught dyeing. Estes’ responsibilities included running the woodworking shop and the sawmill. His skill in cabinet making and lathe work were a decided addition to folk school talent. While Estes was not a carver, it is likely he may have helped out with or supervised the making of the roughed out blocks prepared by the school and given to the carvers. The roughed out shape was then carved with a pocketknife. Members of the Brasstown carvers community cooperative produced small animal figures, a hallmark of folk school craftwork. Estes concentrated on the lathe and on furniture. He also followed in his grandfather’s footsteps, making 17 long rifles during his career as a craftsman. 7

In 1946 the John C. Campbell Folk School was approved as a site for veterans training under the GI Bill. While this approval ensured a steady influx of funds to the school, adjustments had to be made. Veterans were not necessarily interested in the Danish folk school model, a “home center of young people growing into cooperative understanding.” Instead, the men were interested in hands-on experience at the lathe or the forge. During the 1940s, two male teachers taught the incoming GIs: Oscar Cantrell taught blacksmithing at the forge and Herman Estes taught furniture making. The veterans built furniture for their homes and a wagon for the school farm. During the mid 1940s the school enjoyed full enrollment with veterans on a waiting list to enter. Estes also participated in community events at the school and served as Boy Scout leader for a newly formed local troop. 8

In the mid 1950s, Herman Estes retired from the folk school. He and Mabel used the contacts they made at the school to start an independent wood turning business. As a team, they specialized in lathe work, mostly making bowls and platters. Their work ranged from small 5” salad bowls to 28” mixing bowls and plates ranging from 6” to 18”. The bowls were made from a solid piece of wood; three pieces of wood were glued together before a platter could be turned. They used local woods: cherry, maple, butternut, walnut, and sycamore. Herman and Mabel worked out a system in which they took turns working on a single piece. Mabel Estes planed lumber, cross cut it, and “glued it up.” Herman would use the band saw to cut out the rough shape and Mabel would affix it to the lathe. He turned the form and she did the finish work, sanding and sealing it. They sprayed lacquer onto non-food pieces and, to make servingware food safe, they boiled the bowls and plates in olive oil. Together they drove up and down the East coast, lining up 16 shops to sell their work. Herman and Mabel Estes continued to work full-time at wood turning until the early 1960s when they cut production in half. In 1963 they went into “retirement,” but continued to supply four of their favorite shops. 9

- M. Anna Fariello, 2008

1 . Marjorie W. Rogers, “A History of Herman Baker Estes,” (undated) in the collection of the John C. Campbell Folk School; Edward DuPuy, “Interview with Herman and Mabel Estes,” Feb. 3, 1965 in the collection of the Southern Highland Craft Guild, 2.

2. DuPuy, 1. Berea listed a woodworking course in 1900, in “Berea College: Announcements,” Berea Quarterly 5, no. 1 (May 1900): 54; the quotation and a photograph with the caption “Furniture of Ancestor’s Oak” is in a hand-dated brochure, titled “Fireside Industries at Berea College,” both in Berea College Archive.

3. Herman B. Estes, “Herman B. Estes Brasstown, N.C.” (undated) in the collection of the Southern Highland Craft Guild.

4. Rogers; DuPuy, 1-3.

5. DuPuy, 2.

6. DuPuy 1-3.

7. Chris Andrus, “An Interview with Herman Estes,” in the collection of the Southern Highland Craft Guild.

8. John C. Campbell Folk School 29 [school newsletter] (Oct. 1947).

9. DuPuy 2-3.