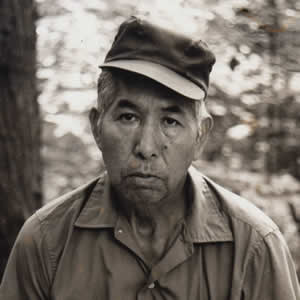

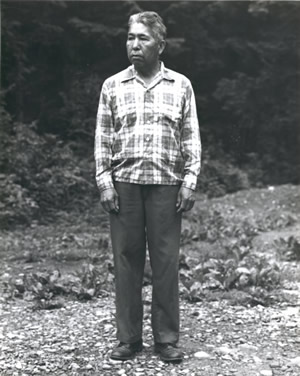

People: Allen Long (1917 - 1983)

Mask maker Allen Long (1917-1983) was the son of Will West Long (1870-1947), Cherokee medicine man and an authority on Cherokee cultural traditions. Born in 1917, when he was 12 years old, Long learned how to make masks from his father. He made a variety of masks including the booger mask, medicine man, warrior, and wildcat. Primarily, Long used buckeye to carve his masks and finished them by staining them with shoe polish, a technique he used instead of the traditional red clay stain which was not permanent. In 1975, the Indian Arts and Crafts Board and Qualla Arts and Crafts Mutual honored him with an exhibition of his work.

Like many Cherokee carvers, Allen Long learned his craft from his father. Few, however, had fathers who were so skilled or so well known. Born and raised in the Big Cove community of the Qualla Boundary, Allen Long was the son of Will West Long, “considered by historians of Cherokee culture to be the authoritative scholar of Cherokee customs during his lifetime.” Allen first learned to carve around 1929, when he was about twelve years old. His woodcarving focused on masks that were used in social and ceremonial dances. “I remember, back a long time ago, they used to put on masks and dance all night,” he recalled. Too young to join in as a dancer, Long watched the ritual events. He also watched his father carve masks that were worn by dancers. His father started him making small masks “about three or four inches in size.” By the time he was eighteen, Long graduated to making life-sized face masks, “preparing for the day when I would succeed my father as the mask-maker of our people.” Long explained that, “Mask-making wasn’t done by just anybody. It was something that was handed down to just certain ones. My father said it had always been so.” But in just a few more years, Long claimed that the dances died out. “I was about twenty when they quit everything. They just quit all at once,” he said.

By the time he was interviewed in 1975, Long was described as “the last surviving link to what was once a viable art form, now in danger of becoming extinct.” Long, like his father before him, carried on an authentic tradition. He made traditional bear masks, painting them black with red dye surrounding the eye holes. But Long followed tradition only to a point. He used buckeye and groundhog skin to make a number of masks, but departed from tradition in the finish of his work. Where his father used red clay and wild root dyes to color his masks, Allen Long used shoe polish to create a dark finish. This was more permanent than the natural dyes that came off on your hands, he explained.

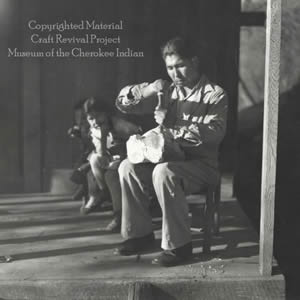

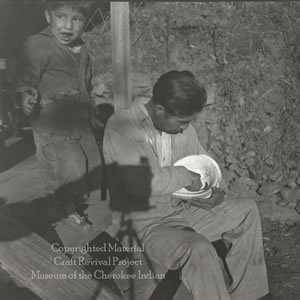

Long’s preferred mask-making material was buckeye, a wood that is soft and easy to carve. The grain of buckeye is prominent and Long used this variation in the grain to give expression to his finished pieces. He selected trees and cut them along Bunches Creek, and at times, purchased wood from others. He explained the process of preparing the wood: “I let the buckeye wood dry out a long while before carving on it. The wood has to be completely dry before painting, or it will come off. I saw the buckeye wood into sixteen-inch sections, and I can get two masks out of that. If I work steady, I could turn out a mask in a day.” Using chisels and a mallet, Long made each mask individually, with no set pattern. Starting with a rough idea, he noted that, “eventually the mask emerges.” He finished the details of each mask with a pocketknife, using carving tools for the eyes and facial details. Of the dozen different masks that Long made, the snake mask was his favorite.

Allen Long was a member of Qualla Arts and Crafts Mutual and sold most of his work through their storefront outlet. He did not carve full-time because, even though he was a successful artist, he thought he would have a hard time making a living by selling his work. Still, his masks were a sought after item and he demonstrated his prowess by consistently winning awards at the annual Cherokee Indian Fair. In 1975, the co-op honored him with an exhibition, producing a brochure titled, Allen Long: Cherokee Mask-Maker. The brochure included an interview and pictures of thirteen masks, including booger masks, buffalo masks, bear and wildcat masks. The masks were not all carved; some were made from gourds and others from hide. One mask was made from a hornet’s nest. The brochure explained that Long had been commissioned by the Indian Arts and Crafts Board to produce this series of masks in “an effort to revive the tradition of mask-making.” The exhibit was co-sponsored by the North Carolina Arts Council.

Anna Fariello

Excerpted from Cherokee Carving: From the Hands of our Elders, 2013

Works Cited

Bockhoff, Esther. “Cherokee Carvers: The New Tradition,” The Explorer 19.3 (1977): 4-11.

Gaynes, David. Artisans / Appalachia / USA (Boone, NC: Appalachian Consortium Press, 1977).

Indian Arts and Crafts Board. Allen Long: Cherokee Mask-Maker (Cherokee, NC, 1975).

Parris, John. “Allen Long May Be Last Cherokee Mask-Maker,” Asheville Citizen-Times (14 September 1975).