People: Nancy Bradley

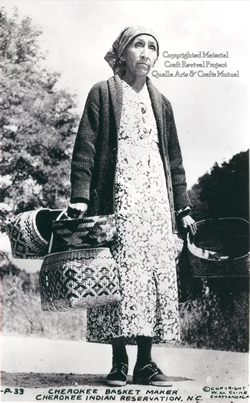

Nancy Bradley’s name is often associated with high quality basketry. “She was the best…Her work was exquisite,” one craft shop owner recalled. 1 Nancy George Bradley (1881-1963) made baskets all of her life, selling them to neighbors and local businesses in trade for groceries. She was married to Henry Bradley, Principal Chief of the Eastern Band from 1947 until 1951. The couple had 8 children. Their youngest daughter Rowena was also a renowned basket weaver. Even though Bradley was born before Cherokee became a tourist town and did not speak English, her baskets received acclaim. She was included in Rodney Leftwich’s Arts and Crafts of the Cherokee and Sarah Hill’s, Weaving New Worlds: Southeastern Cherokee Women and their Basketry. Bradley was one of only a few weavers who knew how to make traditional doubleweave baskets.

Nancy George Bradley (1881-1963) was raised in a basket making family, although little is recorded of her early life. Her mother, Mary Dobson (b. circa 1857) was one of a few Cherokee basket weavers who used white oak in combination with the double weave technique usually associated with rivercane basketry. Her daughter, Nancy Bradley made rivercane baskets and also worked in white oak and honeysuckle. Nancy Bradley was thought to be one of only a few basket weavers who knew how to do the complex double weave technique in the 1920s and 1930s, before it was reintroduced in the Cherokee schools. Nancy Bradley and Mary Dobson only spoke Cherokee, but they managed to sell and trade their baskets locally. Many of their baskets made their way into collections and museums.

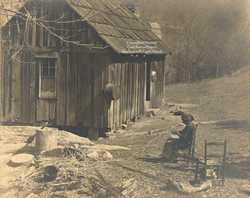

Little changed during the period of Cherokee basket weaving that included Nancy Bradley and her daughter, Rowena. An historic photograph of Nancy Bradley shows her making a basket, working out-of-doors in front of her cabin. A half-century after this photograph was made, Rowena Bradley was interviewed. A description of that day could just as well describe either mother or daughter, making baskets at home.

That spring morning, Rowena Bradley was sitting in a kitchen chair at the edge of her front yard. Dogs slept fitfully nearby; a cat stared from the window, and hens pecked nervously at the ground. Looking out toward the mountains as she wove a rivercane basket, Rowena Bradley followed with her fingers a pattern that lives in her memory. Occasionally selecting a cane split from a bucket half-filled with water, she wove quickly, scarcely pausing to examine her work. She knew without looking how the pattern would develop in the basket. She has woven rivercane baskets most of her life. 2

|

|

| Nancy Bradley made baskets from rivercane that she dyed using native plants | |

Nancy Bradley was married to Henry Bradley, Principal Chief of the Eastern Band from 1947 until 1951. The couple had 8 children. Rowena Bradley recalled that her mother made many baskets.

My mother made baskets day in and day out, except on Sunday…It wasn’t many that made rivercane baskets, but I know she made them. She never quit making them until she got old and she couldn’t see too good. And I don’t think she been quit a year whenever she died. 3

She went on to explain how baskets were used in their family life. Nancy Bradley made and used,

A big old white oak basket, like in the summertime of the year…she’d go down and gather onions and cabbage and beans, you know, potatoes. A big oak basket, that’s what she’d put them in. And my dad usually carried one. He carried stove wood in it. 4

Nancy Bradley’s generation seldom sold baskets outright. There were few outlets in the town of Cherokee that bought and sold baskets. Instead, her generation bartered, trading baskets for things they could neither make nor grow. When she accumulated as many baskets as she could carry, “She would tie them up in an old sheet and throw them across her shoulder and take them to Cherokee to trade for groceries,” Rowena Bradley recalled. 5 Finished baskets—rivercane, white oak, and honeysuckle—were exchanged for groceries and other necessities. A generation later, Rowena Bradley was selling baskets in much the same way. She often walked from her home in Painttown to a store at Soco Creek. “Like other weavers, she could only trade as much as she could carry and could only bargain for what she was able to walk back home with.” 6

While many things have changed from generation to generation, in the late 19th and early 20th centuries, the memories of Cherokee basket weavers indicate a persistence of tradition. The continuity of their work, their materials, and designs make basket weaving an enduring aspect of Cherokee culture.

Anna Fariello

Excerpted from Cherokee Basketry: From the Hands of our Elders,

Published by The History Press, 2009

1. Sarah H. Hill, Weaving New Worlds: Southeastern Cherokee Women and their Basketry (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1997) xv.

2. Hill, 251.

3. Hill, 251.

4. Hill, 251.

5. John Parris, "Turning out the Double-Weave Basket, Asheville Citizen, circa 1974.

6. Hill, 263.