Making History:

Crossnore School

Dr. Mary Martin Sloop, a medical doctor, moved to Avery County, North Carolina in 1911. Within a few years, Sloop was working with the Crossnore community to upgrade a little one-room schoolhouse to expand local educational opportunities. Crossnore School was incorporated in 1917 and continues today. In 1920 Crossnore established a weaving program, operated with funds from the Smith-Hughes Act, federal legislation enacted to support vocational education. Local women wove rugs and coverlets that were sold through the school. After 1935, with the construction of the school’s Weaving Room, women came to campus to weave. From the 1920s into the 1950s, the program was run by Lillie Clark Johnson (Mrs. Newbern Johnson), known to all as “Aunt Newbie.”

Like other western North Carolina weaving programs, Crossnore’s first weaving program was modeled after Berea College’s Fireside Industries. Although Berea became known for teaching weaving, its early Fireside Industries program operated more like a local cooperative rather than an educational program. Berea bought coverlets from local women who did weaving in their homes; finished work was sold through the school. Similarly, through Crossnore’s Weaving Department, local women—“mountain mothers” as Sloop called them—wove bedspreads and rugs in their homes. Eventually, Crossnore built a “Weaving Room” to house its crafts program.

Money for the Crossnore weaving program came from the Southern Industrial Education Association, the Daughters of the American Revolution (DAR), and the Smith-Hughes Act. Dr. Sloop 1 raised funds through the sale of used clothing.When the Weaving Room burned in 1935, Sloop appealed to the DAR who helped construct a more permanent building in stone. Today’s Crossnore campus has many stone buildings, including the 1930s weaving building that houses a museum and retail shop.

Used clothing sales funded early school programs

Reproduced with permission from the North Carolina Collection, Univ. of N.C. Library at Chapel Hill. Bayard Wootten; Wootten-Moulton Collection.

The following is transcribed from The Weaving Room of Crossnore School, Inc. by Philis Alvic, 1998.

On April 6, 1921 Nell Johnson recited her commencement address, "The Art of Handweaving" from memory at the first graduation to take place at the Crossnore High School. She had been assigned her topic by Mary Martin Sloop. Mrs. Sloop summoned Nell back from the Berea Academy in Kentucky to be half of the first high school graduating class. Gurney Franklin comprised the other half of the class, delivering his address on agriculture. While attending high school at Berea, Nell learned to weave from Edith Matheny, the wife of the Academy's Dean. Research for her paper on weaving had been largely drawn from a pamphlet on domestic industries by the Art and Craft Movement designer, Candace Wheeler.

When Nell gave her graduation speech, weaving instruction had been offered at Crossnore School for the previous school year. Sloop modeled the weaving program after the Fireside Industries at Berea College which provided weaving instruction to both school students and women from the community. Crossnore assumed the role of marketing the items produced, as had Berea. The weaving started when money became available for teachers' salaries through a state administered federal program known as Smith-Hughes. The United States Congress passed the Smith-Hughes Vocational Education Bill on February 23, 1917, and thereby entered into a partnership with the states to provide training in agriculture, home economics, and trades and industries.

The weaving program started in the 1920-21 school year with Clara Lowrance and Zada Benfield as the first teachers. A report of the weaving class to the State Department of Public Instruction, Division of Trades and Industries for the fall of 1922 lists a well-developed program of 30 young people and four married women after just two years of operation. 2 An early photograph shows weavers Zada Benfield and Marion Brown seated at small handlooms designed for use in weaving programs by Anna Ernberg of Berea College. The looms commonly used for domestic weaving in the Appalachian Mountains had imposing superstructures of rough-cut timber and took up the better part of any room. Ernberg fashioned an all-wooden loom that fit together without hardware and could be easily copied by a competent woodworker.

Money also came from the Southern Industrial Education Association to develop a community component to the weaving program. Martha Gielow founded the Association in 1905 to encourage handicraft projects in the southern mountains. The Association ran an Exchange in Washington, DC that sold crafts. Ellen Wilson, first wife of President Woodrow Wilson, decorated a room in the White House using weaving commissioned from mountain women through the Exchange. In the Association's newsletter for the fall of 1924, Mary Sloop reported on the effectiveness of the program: "It is not only a material help to them, but it makes a change in their attitude toward life, and for this reason we feel that the money given us by the Southern Industrial Education Association is bearing fruit in the lives of the women."

Raised in Texas, Clara Lowrance attended Presbyterian higher education schools and started teaching at Crossnore in the early years. During the first part of the 20 th century, many educated women from around the country taught in the over 150 Appalachian independent schools founded by church missions or philanthropic organizations. A newspaper report at the time of Clara's death in 1958 stated that she learned to weave at Berea College during vacation time from her job at Crossnore. Miss Lowrance supervised Crossnore's weaving from its inception until the 1925-26 school year. The other teacher, Zada Benfield, grew up in Crossnore and attended Normal School at Berea where she learned to weave. Zada left her position after only one year to marry. On the Final Report form submitted to the state Miss Lowrance took advantage of the "Remarks" column alongside the grades to comment on her students. Some received praise: “Does beautiful work…Does as well as any one could…Very careful and thoughtful." Others garnered severe statements: "Rather talk to the boys than work...Too many children to weave much or well...Expects us to do her work...Without patience."

When Clara Lowrance left Crossnore in 1926, Lillie Clark Johnson assumed leadership of the weaving program. Lillie Clark had grown up in the Crossnore area, married Newbern Johnson, and had three children before learning to weave. Mrs. Johnson, called “Aunt Newbie” by all who knew her, assisted Lowrance and was listed as "teacher" beginning in 1923. Prior to that she appeared in the list of students and received the grade of “Excellent” for her class participation. She came to the Weaving Room to work rather than having a loom at her home like most of the other women.

At the bottom of her June 1923 report, Miss Lowrance commented, "Have girls and boys wanting to take lessons. But do not have handlooms and room. Can do better when we get more equipment and our new building which we hope will be finished by August." In the early years the weaving took place in a cinder block building on the campus, but the program quickly outgrew this space. In 1929 with the help of five chapters of the DAR from Charlotte, two log buildings were moved to the site and joined together to serve as the new weaving home. Timber companies heavily logged Avery County during the early part of the century. Therefore, building materials did not grow nearby. At Penland the weavers donated logs and helped in construction of their own Weaving Cabin. The largest part of the Crossnore structure came from a barn that had belonged to the notorious McCandless gang that rode with Jesse and Frank James. Uncle Will Franklin contributed the other half. The two barns joined at an. unusual angle to fit the small plot of flat land available along the main road through town. In the two-story building with lots of windows, sewing classes and rug hooking production occurred in addition to the weaving. The log Weaving Room had a sales display area for tourists.

In the fall of 1924 Crossnore reported to the state that 38 students worked at school looms and 11 women wove at looms in their homes. The students each spent an average of 120 hours weaving between July and the end of December. However, no one actually worked that average time. Essie Ollis out-performed all of the others by several hundred hours, racking up 712. After Essie married, she became Mrs. Johnson's assistant in the Weaving Room. Pheba Benfield's 388 hours ranked second in the class. The wide variance in hours reflected the casual policy that existed in the Weaving Room: students worked the time that they wanted. No one required them to come at a certain time or maintain a set number of hours in a period. Even though the students decided their own work schedules, the supervisor maintained accurate records and reported to the state twice a year. The home workers all received payment on a piece rate basis, but the students could be paid either by the hour or by piece rate. Some early weavers remember being paid 10 cents an hour as students. While ten cents does not sound like much by today's standards, some men working on the Blue Ridge Parkway construction in the mid 1930s were paid 12 cents an hour for rock work.

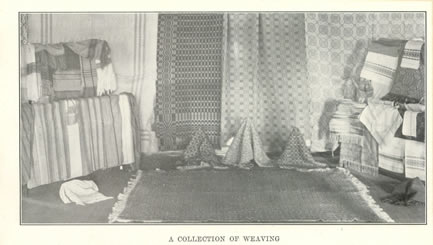

This “Collection of Weaving” appeared in a Crossnore sales brochure

During their time spent in the Weaving Room the students produced items for sale. Instruction took place as they advanced to pieces involving more complex techniques. As the Weaving Room assistant, Essie Ollis Perrell assigned projects and helped the students to master skills. Usually students started with a plain weave structure and, when their work proved satisfactory, moved on to the harder pattern weaving. The criterion for advancing to more complex work was the production of a piece with even beat, neat selvedges, and, of course, no mistakes. The weavers made a full array of items: coverlets, rugs, couch covers, dresser scarves, sofa cushions, bags, guest towels, and baby blankets. Many of these items exhibited refined craftsmanship, and even the high school girls wove coverlets, which required the highest skill.

In a long article in the Raleigh News and Observer for June 19, 1927, Maude Minish Sutton goes into some detail about the development of the school at Crossnore with a section devoted to weaving. Under the headline for the feature, “Crossnore Real Community Work," followed three subheadings: "Experiment In Industry and Education Develops Satisfactory Results,” “Works Miracles in Neighborhood Life,” [and] “There's No Charity About Crossnore In Spite of the Unusual Method by which it Attains Support and The Crossnore Folks Resent the Suggestion." A description of the activities of the Weaving Room includes that the "weaving department cleared $3,000 last year." Sutton gave the types of items made and the coverlet patterns, and discussed Mrs. Johnson mixing dyes for the yarn. "She uses vegetable dyes native to the mountains, and the colors are indescribably lovely." Crossnore wove with natural dyed yarns during the early years, but collecting dyestuffs and the process of dying proved too labor intensive to continue.

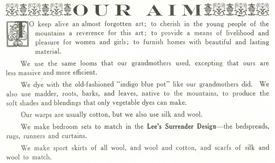

A brochure of the Weaving Room from the early 1920s contains a mission statement and an appeal to the social conscience of consumers. Amid photographs of weaving patterns, the objectives of the program appeared: "To keep alive an almost forgotten art; to cherish in young people of the mountains a reverence for this art; to provide a means of livelihood and pleasure for women and girls; to furnish homes with beautiful and lasting material." Other Appalachian weaving centers listed similar goals of preserving the art of weaving and providing employment to women, and often added a third objective which attributed some character-building property to the act of weaving.

Sutton's article in the Raleigh paper claimed positive social results from the Crossnore weaving program. "Mrs. Sloop says that the weaving department has raised the social and moral status of the community....The sight of beautiful things, the mastery of a beautiful art, and the consciousness of good craftsmanship have given a sort of dignity and prestige to the weaving girls and to the mothers who weave." A quote from one of the women, "Now that I've got a chance to make a little somethin' maybe my own children won't look down on me," highlighted another social good.

In the weaving brochure, Mary Sloop appealed to benevolent middle-class women, stating, "Many mountain mothers may earn money which they need more than you can imagine, and long for, with a longing you have never known. Married as mere girls, with almost no education, they have watched the wonderful development of their younger sisters or their daughters, till their own privations and limitations have loomed large. To these hungry minds the weaving lessons open new fields." Even though the weaving came about through a Smith-Hughes program for high school students, supplying work for community women was a major component.

So there would be no ambiguity in the minds of prospective customers about a desired course of action, Sloop noted that, "Life is a different thing to these 'hidden heroes,' as I call these mountain mothers, and you help to produce the result when you enable us to sell their finished product. SO, WHO WILL BUY?" This approach must have proved satisfactory because the pamphlet was reissued over several years with the only changes listing a new director and price increases. The brochure would have been sent to a growing list of Crossnore supporters, women's clubs, and church groups. Products of the Appalachian Craft Revival found consumers through a women's network that existed largely outside of the commercial world where middlemen and shop owners exacted part of the profits. The mountain weaving centers provided a greater percentage of the purchase price to the weavers than would have been generated through customary commercial venues.

Besides the brochure the weaving sold through organized sales events sponsored by organizations of social concern. In one of Mary Sloop's fund-raising letters she asks, "How about a Christmas box? Let us send you one from our Weaving Dept. and see if you cannot choose your Christmas presents from it, and maybe you would like to exhibit goods at your Club, D.A.R. or D.D.C. or a Church Social and let the members choose their Christmas gifts. You may return to us what you do not sell and we know of nothing that can be a greater help to us than to help us market our goods." The weaving also sold to tourists who came to the mountains in the summer. While second homes and resort hotels had long been part of the mountain landscape, the automobile gave access to more visitors in the 1920s. The Blue Ridge Parkway, planned in 1933, also drew tourists to the area.

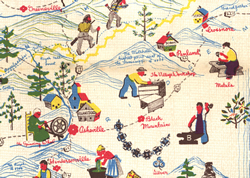

Shortly after Christmas in 1928, a delegation of four—Mrs. Sloop, her daughter Emma Sloop, Mrs. Johnson, and school trustee McCoy Franklin—represented Crossnore at the discussion of the founding of an organization of Appalachian craft production centers. Delegates came from eleven centers in Kentucky, Tennessee, and North Carolina to the meeting held at Penland, North Carolina. They desired some joint vehicle to study common problems of handicraft manufacture and to cooperatively market their products. Members of this group became acquainted with one another during the meetings of the Conference of Southern Mountain Workers held each March in Knoxville. John C. Campbell founded the conference with backing from the Russell Sage Foundation when he realized that Appalachian institutions run by philanthropic organizations often knew very little of the work of other similar endeavors. He felt they would benefit from jointly studying common problems and sharing information about effective programs. John C. Campbell, with help from his wife, Olive, functioned as the Southern Division of the Russell Sage Foundation, and gathered information for the first serious sociological study of the Appalachian, The Southern Highlander and his Homeland. 3 Shortly after the death of Russell Sage in 1906, his wife established a foundation in his name and began giving away his millions in the cause of social betterment.

Allen Eaton recorded the cooperation of the weaving and other craft production centers and their organizational meetings in a chapter of his book Handicrafts of the Southern Highlands, published by the Russell Sage Foundation in 1937. Several people present at the first gathering shared stories of their work and the mountain area. Mary Sloop read from portions of Uncle Jake Carpenter's “Anthology of Death on Three Mile Creek.” During sessions, the representatives laid out the parameters for an organization. The joint venture would address common concerns while each center maintained autonomy in management of their business.

A delegation from Crossnore attended one year later when the group of production centers met at the Spinning Wheel in Asheville to formally organize the Southern Mountain Handicraft Guild. George Coggin of the North Carolina Department of Vocation Education also attended and told of the state's activities in promoting handicraft production and of his desire to work with the new organization. The constitution of the guild laid out five objectives: to encourage cooperation among agencies, to promote a wider appreciation of crafts, to maintain standards, to study common problems, to disseminate information on methods and materials, and to hold workshops. The organization, which soon changed its name to the Southern Highland Handicraft Guild, met twice a year: once in conjunction with the Conference of Southern Mountain Workers, and again during the fall in the territory of one of its members. In the first three years the organization membership grew to 25 centers and 12 individuals with nine “Friends” from the nine initial centers, one individual, and two friends.

On October 10 of 1933, the group convened at the Weld House in Altamont a few miles from Crossnore. The next day the second business session met in the Weaving Room at Crossnore. There, Allen Eaton told of the success of an exhibition organized by the guild and circulated by the American Federation of Arts, which had opened at the Country Life Association conference in Blacksburg, Virginia, and would soon be shown at the Corcoran Gallery in Washington, DC, and later travel to the Brooklyn Institute of Arts and Science. This exhibition of mountain crafts eventually visited a total of 10 venues around the country. Of the nearly 600 handcrafted pieces in the 1933 exhibit, over 300 items came from weavers. Crossnore sent 23 pieces under 10 different item names: runner, napkins, baby blanket, place mats, couch cover, spread, steamer throw, skirting, pillow cover, and bags. The bags required some construction, but all the other items had only end finishing or straight joining. The couch covers differed from spreads in width. The spreads or coverlets consisted of two fabric lengths sewn together, while the couch covers were woven in a single panel 48 inches wide. The catalogue from the exhibition names patterns for some of the pieces. The overshot patterns of Lee's Surrender, Martha Washington, Pine Bloom, Chariot Wheel, and Governor's Garden, have remained Crossnore favorites.

- Philis Alvic, The Weaving Room of Crossnore School, Inc.

(Avery County, NC: Avery County Historical Society and Museum, 1998)

Used with permission of Philis Alvic

See More: About Crossnore School

1. For a first-person account of Sloop’s life and work, see Mary T. Martin Sloop. Miracle in the Hills (New York: McGraw-Hill, 1953).

2. Philis Alvic. Weavers of the Southern Highlands ( Lexington: University of Kentucky Press, 2003) 119. Alvic cites a 1922 report from the North Carolina Department of Vocation Education at the North Carolina State Archives.

3. John C. Campbell. The Southern Highlander and His Homeland (New York: Russell Sage Foundation, 1921).