The People:

Murray Martin

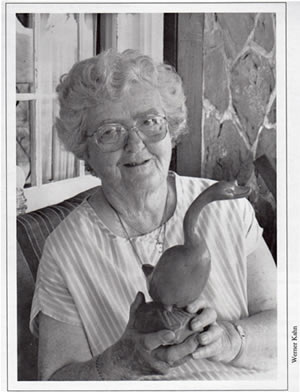

“I’m eighty-eight years old and can’t carve, but now I’m painting.” Murrial "Murray" Galt Martin (1903-2005) taught carving at the Folk School from 1935 until 1973. “I carved some before I came to the Folk School.” She still has her first St. Francis carving, roughed out by Ben Hall. “Rufus Morgan, an Episcopal minister, requested the first St. Francis figure...he said St. Francis was his patron saint.” Murray points out that she mistakenly put the rabbit on St. Francis’ shoulder and the bird in his hand.

“When I first came to the Folk School my future husband (Dub) later told me he was the one who carried my trunks up to the guest room in Keith House.” Coincidently Dub Martin’s mother and father were both carvers. Murray continues,”...at the time I didn’t think I would last a month or two...the Lord sent me to meet Dub and the Folk School, and I’ve had an awful good time since I’ve been down here.”

Murray originally worked as an occupational therapist at Walter Reed Hospital primarily teaching weaving. Mrs. Campbell, the Folk School’s founder, wanted someone who could work well with people and teach design. She wrote Mrs. Emmy Summer, a Dane and the Director of Occupational Therapy at Walter Reed. Murray was recommended to be interviewed in Washington, D.C. by Louise Pitman, who headed the Folk School’s marketing program. Murray was offered and accepted the position without any knowledge of where Brasstown, North Carolina was. To this day she doesn’t qualify herself as a carver and proudly exhibits a quote from Mark Twain that, according to Murray, symbolizes her success at the Folk School, “All you need in this life is ignorance and confidence and then success is sure.” Mrs. Campbell found the teaching designer she was looking for in Murray and most will agree Murray is definitely a fine carver, “We all quietly worked it [carving] out together.”

Murray taught all the crafts when she first began at John Campbell, “You know I was a weaver...I taught the girls weavings, capes, runners, knitting...I had to teach all the crafts, that’s way back.” She taught her carving students to observe, study farm animals and the creatures of the woods, “If you’re going to carve a pig, go look at one.” Oftentimes Murray would bring an animal for the carvers to observe first hand, place it on the carving table and have the students touch it and look at it from every angle. Her years at the Folk School “was a wonderful experience...it thrills me to death to see successful work of one of the carvers,” She continues, “Many of the carvers had a lot of talent in their fingertips, especially in Warne...at one time there were seventy-five carvers...I always called them community carvers.”

Murray says that carving didn’t always come easy to the carvers. Mr. Ben Hall often joked that “...he would wear out his carving carrying it around in his pocket before I would accept it.” There were people who would come up to Murray and say, ‘I sure would like to try and carve that’, those were the ones who became carvers. When pressed to mention who had been some of the best Brasstown carvers, she smiles and says, “Ben Hall, John Hall, Avery Beaver, Jack Hall...he was a very fine carver...the first time I saw Avery, he was on a riding horse...I asked him would you like to carve that horse and he said he sure would. I made a drawing and gave him a block.” When Queen Elizabeth [then princess] visited America she purchased two of Avery’s colts in a Pennsylvania shop, and later she wrote the shop owner to express how much she liked the carvings...when I asked Avery if he was proud, he just said, “I take each day as it’s handed out to me.”

Murray designed the Folk School’s now famous crèche figures, “People would send pictures and other carvings to us, but I wanted the carvers’ crèche figures to be their own. Ben Hall was the first to work with me...he did the first cherubs, and Hope Brown, the angels. The first were in pine; that didn’t work, then apple, finally holly; it looked like ivory. We were lucky in that we had a great source of fine woods available for free when the TVA cleared land for reservoirs.”

“Carving napkin rings was a life saver...I got the idea looking at scarps sawn off the ends of carving blocks...my husband and I worked them out together and I would give them to beginners, then I designed napkin rings after napkin rings,” Murray concludes, “I’m glad I was here in the early days...Mrs. Campbell was my inspiration. She believed in me so I had to do something...You know Ron Hill is one fine director too.”

When asked about the current carving instructor, Helen Gibson, Murray brightens, “See I’m very proud of Helen...I taught her mother [Dot McClure]. Helen started with Mrs. Ivester; later she would sit down with me and we’d work out carvings, and when I still carved, I was working on the Mary crèche, and when I got to the face I couldn’t see the detail on account of my eyes...I went to Helen to help me carve Mary’s face, and she happily did it for me.”

One of Murray’s fondest memories, that sums up a carvers love for his art, is seeing Ben Hall gently stroking one of his fine carvings and saying, “Here is the pleasure.”

- Transcribed from John C. Campbell Folk School, The Brasstown Carvers (1990),

with text by Bill Biggers, photographs by Werner Kahn and Bill Biggers.

Used with permission of the John C. Campbell Folk School.

See More: Carvings and Writings by and an Interview with Murray Martin