People: Cora Arch Wahnetah

Cora Arch Wahnetah (1907–1986) was born into one pottery family and married into another. She learned from her mother, Ella Long Arch (born 1889), and both her maternal and paternal grandmothers were recognized potters. Her childhood memories included happy hours spent collecting clay with her family on Soco Creek. While aware of modern methods and once described as an “ingenious contemporary potter,” Wahnetah was faithful to older pottery traditions. She preferred simplicity, eschewing the wheel in favor of hand-formed, pit-fired work. She spoke openly of finding inspiration not in the work’s economic value but in the process of making the work itself. Wahnetah was a presence in the beginnings both of the Oconaluftee Indian Village, where she demonstrated pottery techniques, and the Qualla Arts and Crafts Mutual cooperative, which provided her with a local outlet to sell her wares and which she credited with raising the quality of Eastern Band craft.

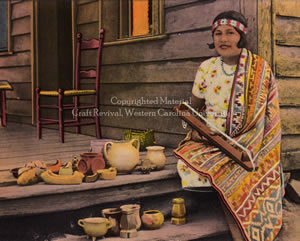

Cora Arch Wahnetah (1907–1986) learned the techniques of both coiled and modeled pottery from her mother, Ella Long Arch (born 1889), who at sixteen married Johnson Arch, grandson of potter Jennie Arch. Ella Arch remained an active potter into the 1930s and was described as “an independent, a rugged individualist” by anthropologist Raymond S. Stites. A series of postcards promoting Cherokee crafts featured one with Ella Arch posed with her daughter-in-law, Sarah, who is burnishing a pot in her lap, and Cora, who is stringing a bead loom.

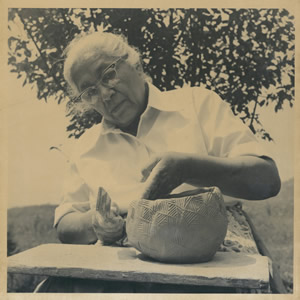

Cora married Samuel Wahnetah, the grandson of Catawba potter Susannah Owl. Wahnetah’s ties to the Catawba tradition were not as strong as those of her mother’s generation, but she did grow up within that same small circle of native potters. She remembered spending “many happy hours” on all-day trips with her family to dig clay on Soco Creek, traveling by horse and wagon. While quite aware of modern methods, Wahnetah consciously worked within the parameters of tradition. “I have never made any pottery on the wheel because I do not like to make any two pieces alike,” she said. Citations for her work often included statements referring to her preference for simplicity, with a 1971 exhibition brochure describing her process as using “simple wooden hand tools” and pit-firing methods. 1

Vessel with incised surface |

Vessel with modeled appliqué animal shapes |

As she became a potter in her own right, Wahnetah learned about older pottery traditions. She worked closely with Madeline Kneberg Lewis, an anthropologist from the University of Tennessee in Knoxville who had been hired by the Cherokee Historical Association to draft a plan for a proposed reconstructed village that would serve as a living history museum for the tribe. Once opened, the Oconaluftee Indian Village featured Cherokee people at work in costumes based on tribal clothing from circa 1750. In an interview, Wahnetah said that Kneberg “taught me just all I know about the ancient method” of making pottery. But it appears that the relationship was more a collaboration than Wahnetah’s modest statement reveals, as Kneberg cites Wahnetah’s methods in her report. While most of the pottery section in Kneberg’s 1954 plan references Mooney and Harrington, it was Wahnetah who assisted the anthropologist in developing the mechanics of making pottery at the village, and after the village opened, Wahnetah worked there as a demonstrator. 2

Vessel with highly burnished surface |

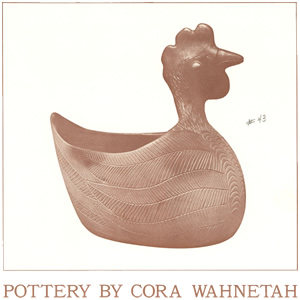

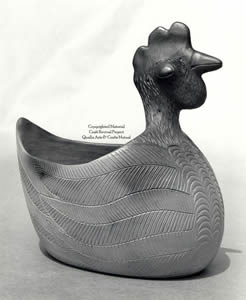

Modeled hen form |

As she did with forming her pottery, Wahnetah followed the “ancient method” of firing it. She pit-fired her hand-formed pieces using wood, which gave her work a “distinctive dark and evanescent wood-smoked finish.” This method was not learned from her mother, who fired work in the oven of a wood cookstove. Wahnetah was exacting with her process: “I have to pick a certain type of day to burn pottery. On damp days I don’t do my burning. It has to be a real sunshiny, clear day. The pottery that’s burned on a dark day—rainy days or damp days—doesn’t turn out as well as if it was fired on warm sunshiny days.” 3

A 1971 exhibit brochure about her work described Cora Wahnetah as “one of the most ingenious contemporary Indian potters of the eastern United States.” In the brochure, she spoke eloquently about her pottery, saying she was inspired not by the work’s economic value but by the process itself.

I make pottery not for the money there is in it but because I love to get my hands in the clay, forming it into any shape I have in mind. I have never made any pottery on the wheel because I do not like to make any two pieces alike. After I watch the vase or pot dry enough to get carving on it, I enjoy the quietness as I work out a vessel and get it ready for the burning. When the fire has burned out, there is pleasure when I find the vessel has burned well, with just the color I like. It is then that I give thanks for my work.

Effigy oil lamp |

Wedding vase |

The exhibition, sponsored by the Indian Arts and Crafts Board, Qualla Arts and Crafts and North Carolina Arts Council, included seventeen “richly-textured decorative” forms. These included effigy bowls, jars, a four-stemmed peace pipe and a wedding vase. While Wahnetah constructed her pottery according to tradition, she was able to produce a wide variety of surfaces, having mastered multiple techniques, including paddling, incising, burnishing and modeling. 4

Paddling a hand-built pot |

Vessel with paddle-stamped surface |

Cora Wahnetah was an avid supporter of Qualla Arts and Crafts Mutual cooperative. Her name does not appear on any of the early meetings rosters, she was a charter member of the guild. Before the formation of the co-op, Wahnetah carried her work to Bryson City and Chimney Rock. Once the cooperative was up and running, she sold almost all of her pottery through this one outlet. She particularly noted the importance of the exhibition series. Besides the exposure, which she acknowledged was important, she thought that seeing the finest crafts helped other craftsmen improve their work. In an interview, she remarked, “Qualla has meant everything to me. … Most of the members would say the same thing. It has helped them a lot.” 5

M. Anna Fariello

Biography excerpted from Cherokee Pottery: From the Hands of our Elders

Published by The History Press, 2011

1. Raymond S. Stites, “Kilns for the Cherokee,” 1935, National Archives and Records Administration, Southeastern Division, Atlanta, Georgia, 6; Cora Wahnetah recorded interview, National Archives and Records Administration, Southeastern Division, Atlanta, Georgia; Indian Arts and Crafts Board, Pottery by Cora Wahnetah (Cherokee, NC, 1971).

2. Cora Wahnetah interview; T.M.N. Lewis and Madeline Kneberg, “Oconaluftee Indian Village: An Interpretation of a Cherokee Community of 1950,” 1954, Cherokee Historical Association, Museum of the Cherokee Indian, 20; Indian Arts and Crafts Board, Cora Wahnetah.

3. Cora Wahnetah interview; Indian Arts and Crafts Board, Cora Wahnetah.

4. Cora Wahnetah interview; Indian Arts and Crafts Board, Cora Wahnetah.

5. Cora Wahnetah interview. Her name is sometimes spelled Wahyahneetah.