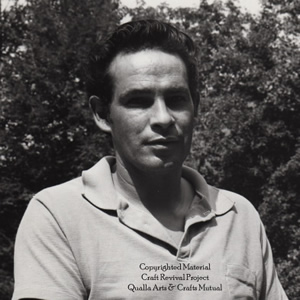

People: Virgil Ledford (b. 1940)

Virgil Ledford (b. 1940) was born in the Birdtown Community on the Qualla Boundary. He is a member of the Eastern Band of Cherokee Indians. Ledford began carving as a child while still in elementary school; his grandfather was also a carver. Later, he studied with famed sculptor Amanda Crowe. Throughout his life, Ledford carved detailed images of wildlife animals that are native to the region's eastern forests. In 1974, he was honored with a solo exhibition at Qualla Arts and Crafts Mutual where he exhibited 21 pieces in cherry, buckeye, walnut, and mahogany. The exhibition was accompanied by a four-page brochure produced by Qualla Arts, the Indian Arts and Craft Board, and the North Carolina Arts Council.

Virgil Ledford once said, “I would rather carve than eat,” a testimony to a truly creative nature. Born in the Qualla Boundary community of Birdtown, Ledford recalled that he started drawing animals on pieces of wood while he was still in elementary school. A teacher recognized his talent and encouraged him by buying his first carvings. “I should have been doing my schoolwork,” he recalled, but his desire to draw and carve outpaced other interests. “I picked up a piece of wood one day at home...I think a little piece of pine board...and I drew a horse on it. I took a mountain knife and outlined it and then shaped it up.” He later realized that he had created a bas relief. “These first carvings were of animals that were often seen in the woods around my home,” he remembered, noting how a love of wildlife inspired much of his work. In high school, he studied with Amanda Crowe, and it was under her instruction that his “greatest growth was achieved.” During those high school years, Ledford was enrolled in a three-hour carving class that met every day. “It was Miss Crowe who taught me to think for myself in creating designs of a contemporary nature as they related to the history of native land and people,” he explained. Ledford has continued to build on a repertoire of forms that relate to traditional culture, choosing animal and human subjects that are common to Cherokee life.

As an adult, Ledford moved to Soco where he lived with his growing family. After trying out a job as a mechanic, he realized that he could provide support for his family by carving if he approached his avocation as a full-time occupation. Staying at home with his children, he often carved ten hours a day. “I find that I can make more money as a carver than I can working at a public works job, and this is what I really enjoy doing.” Given his dedication and the fine quality of his work, Ledford found no difficulty in selling his pieces. “People are waiting for my carvings,” he said.

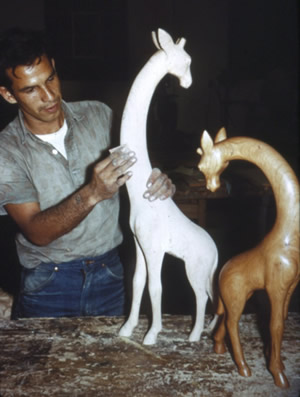

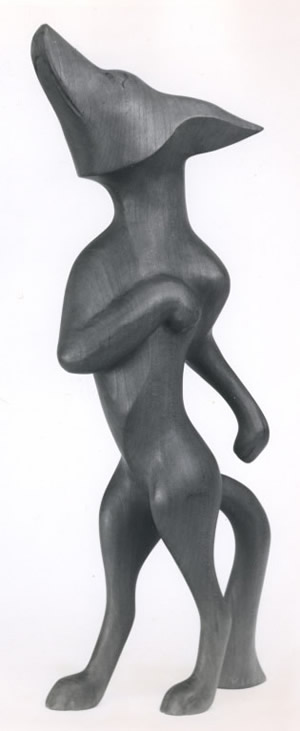

Ledford has his own style and remarked on its importance. “You can’t carve like somebody else,” he advised. “You have got to have your own feeling of what the animal or bird looks like.” Inspired by nature and his immediate environment, Ledford studies real-life animals. He tries to visualize how they would look as a carved sculpture before making a pattern. Since Ledford has always appreciated drawing, he works out the design in pencil. He then traces this sketch onto a piece of wood that had been roughed out with a chisel and mallet or sometimes he makes a cardboard template. He refines the shape using a band saw and uses a pocketknife to achieve finer detail. After sanding, he applies up to six coats of finish, rubbing the polished wood between each coat and finishing with wax. As a professional craftsman, Ledford is innately mindful of sustainable processes. He tries to use an entire piece of wood when carving and, to avoid waste, burns leftover cuttings in his family’s woodstove. He cuts wood for himself or purchases it from a local sawmill or from neighbors. While some artists prefer a single material, Ledford carves using a variety of native woods. Buckeye, cherry, and black walnut are among his favorites. He uses each to a full effect, using the grain of the wood to enhance a sculpture’s overall design.

While Ledford noted that he did not attend art school (no doubt thinking of Amanda Crowe’s degree from the prestigious Art Institute of Chicago), that fact has never hampered his career. His work is sought after and has found its way into many museums and private collections. He explained his inspiration in a 1981 interview. “The more you do, the more imagination you get. I carve one piece and then change it to put in more feeling.” In 1973, the Indian Arts and Crafts Board organized an exhibition of Ledford’s work in the members’ gallery at Qualla Arts and Crafts cooperative. For the show, he exhibited twenty-one pieces. While most of the forms represent animals...an eagle, owl, turtle, and groundhog...he also exhibited a number of human figures. These represent mythic figures, like the Eagle Dancer and End of the Trail, as well as figures common to Cherokee life, like Indian Potter, carved in mahogany. In 1995, Ledford was the recipient of a North Carolina Heritage Award, the state’s highest honor given for traditional arts.

Anna Fariello

Excerpted from Cherokee Carving: From the Hands of our Elders, 2013

Works Cited

“A Treasury of Tar Heel Folk Artists: The North Carolina Folk Heritage Award, 1989-1996,” North Carolina Folklore Journal 44.1-2 (1977).

Bockhoff, Esther. “Cherokee Carvers: The New Tradition,” The Explorer 19.3 (1977): 4-11.

Derks, Scott. “Artistry in Wood,” Wildlife in North Carolina (1981): 6-11.

Indian Arts and Crafts Board. Virgil Ledford: Sculpture and Carving (Cherokee, NC: 1973).

Qualla Arts and Crafts Mutual, Cherokee Artists 2: The Woodcarvers, Film (Cherokee, NC: 1994).