People: Agnes Welch

Agnes Lossie Welch (b. 1925) is known for making white oak baskets. Unlike most Cherokee basket weavers, she did not learn this craft through her family. Instead, Welch learned to make baskets in school, from Lottie Stamper. Stamper taught Welch to weave traditional rivercane baskets; it was only later that she learned to make white oak baskets from her mother-in-law. White oak basketry became Welch’s specialty. Agnes Lossie Welch’s signature appeared with 100 other craft workers who signed on to become members of the newly formed Qualla Arts and Craft Mutual cooperative in 1946. Twenty-five years later, in 1972, the same co-op honored Welch with a solo exhibition of her work.

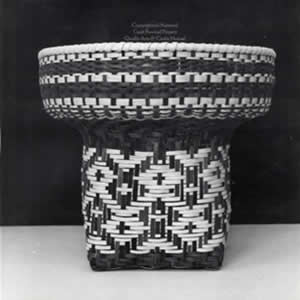

Agnes Lossie was born June 23, 1925 in the Big Cove community on the Qualla Boundary, lands owned by the Eastern Band of Cherokee Indians. In 1937, while she was still a schoolgirl, she learned to make baskets from Lottie Stamper. For 30 years, Lottie Queen Stamper (1907-1987) taught hundreds of girls how to weave baskets. Taking Stamper’s class, young Agnes Lossie was only 12 years old when she made her first basket. “I was the first in my family who learned basket weaving,” Welch remarked in an interview. Home Economics teacher, Gertrude Flanagan gave Agnes Welch a burden basket and asked her to duplicate it. Working with Lottie Stamper, the two weavers worked out the basket’s construction. Agnes Lossie was quick to pick up basket weaving skills. While she was only able to attend basketry classes for one year, she mastered the craft. The white oak burden basket-albeit highly decorated-became her specialty. 1

Agnes Welch’s experience among Cherokee basket weavers was not common; most weavers learned from their mothers and grandmothers. By 1937, when Welch learned to work rivercane, craft traditions had begun to shift. Several factors affected how the region’s craft makers would share traditions and sell their work. New marketing opportunities grew from the establishment of key regional initiatives: the Southern Mountain Handicraft Guild in 1930, the Great Smoky Mountains National Park in 1934, and the Blue Ridge Parkway in 1935. Baskets were no longer limited to home use and became items for sale.

In 1946, Welch learned to make baskets out of white oak. “I learned how to use white oak splints to weave baskets from my husband’s mother,” she recalled. In turn, she taught her own daughter-in-law, Carol Welch, who is known as one of the Cherokees’ most accomplished basket weavers. Although the basketry tradition did not come down to her through her family, Welch explained her connection to tradition as well as her departure from it. She was known for her experiments with dye materials.

“The old Cherokee baskets of white oak were hardly ever dyed. They were just woven and left in their natural color to season and age...[today] I use natural dyes. Mostly blood root and walnut root. Bloodroot makes a yellowish red and the walnut root a dark brown. I put both colors into my baskets.” 2

Welch lived on Galamore Branch, well into the western North Carolina mountains where basket weaving was a way of life. She was proud to have sold enough baskets to buy materials that went into building her house, where she raised 12 children. Like other basket makers, she often worked outdoors at her home. She and her husband raised their family in Big Cove, the same community where Welch grew up. Basket weaving helped buy groceries for her own large family. Her husband helped her gather materials needed to make baskets.

Because oak trees grew abundantly on mountain slopes, white oak became a popular material for making baskets. While oak baskets were made throughout the Appalachian mountains by Native Americans and European settlers alike. By the 1970s, however, Agnes Welch already noticed a decline in this resource.

“My husband cuts the oak saplings for me. But I do everything else. I prepare the materials and do the dyeing and the weaving...The right size of white oak is getting harder and harder to find. It’s got to be from four to six inches thick. If they’re any larger, the grain’s too coarse and tough and won’t peel into splints.”

She explained the process further. After felling the saplings, her husband split them into three-foot sections and then into half-inch strips. “That’s when my work begins,” she said.

“After they are peeled, I take my knife and shave them down smooth. It’s a tedious job. And then I dye them and soak them in water to keep them pliable so I can work them into the basket. They’ll get stiff if you don’t and you can’t weave them at all.” 3

Welch regularly turned out 200 splits a day, weaving them into baskets of every size and function. In a 1972 Asheville Citizen-Times interview, journalist John Parris noted the variety of basket forms that Welch produced.

“She makes baskets of every shape and use-market baskets, burden baskets, pack baskets, shopping baskets, picnic baskets with lid, tray baskets, and baby baskets.”

Welch recalled that she once made a lady’s hat from white oak splits. The hat, made in 1970, and dyed with bloodroot and walnut root, was listed in a brochure printed to accompany an exhibition of her work. 4

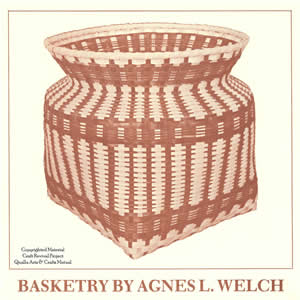

A 1972 exhibition of Agnes Welch’s baskets |

A 1972 exhibition of Agnes Welch’s baskets |

Agnes Lossie Welch’s signature appears with 100 other craftsmen on a 1946 roster of those interested in establishing Qualla Arts and Crafts Mutual, a Cherokee artisan cooperative. Twenty-five years later, the same co-op honored Welch with a solo exhibition of her work, an exhibit sponsored, in part, by the North Carolina Arts Council.

“In the mid-1940s, the Cherokee craftsmen, with the assistance of the Bureau of Indian Affairs and the Indian Arts and Crafts Board, organized their own craft cooperative, Qualla Arts and Crafts Mutual, Inc. With the establishment of their own wholesale and retail outlet, special emphasis and assistance were given to help the individual craft worker improve and market his crafts. As a member of Qualla, Mrs. Welch’s interest in basket weaving was challenged to new heights of individual design and aesthetic achievement.”5

Anna Fariello

Excerpted from Cherokee Basketry: From the Hands of our Elders,

Published by The History Press, 2009

1. Indian Arts and Crafts Board and Qualla Arts and Crafts Mutual, “Basketry by Agnes L. Welch” (Cherokee: Qualla Arts and Crafts Mutual, 1972); Sarah H. Hill, Weaving New Worlds: Southeastern Cherokee Women and their Basketry (Chapel Hill: University of NC Press, 1997) 300.

2. John Parris, “Work Has Earned More Than Money,” Asheville Citizen-Times, circa 1972.

3. Parris, circa 1972.

4. Quote is from Parris; Indian Arts and Crafts Board, 1972.

5. Indian Arts and Crafts Board, 1972.